This well-written Washington Post article written by Fenit Nirappil and Sabrina Malhi validated my thoughts about the apathy towards COVID. As someone who has an immune system disease and who must take immunosuppressants, I could already see and feel it as the data ended, masks came off (in more ways than one), the warnings stopped, and the self-absorbed attitude returned. But to see it articulated in print makes it even worse, & it makes me more angry. Pretending that COVID doesn't exist is not a strategy.

Pass this on to the other COVID-cautious people in your life - if there are any.

COVID will still be here this summer. Will anyone care?

By now, it’s as

familiar as sunscreen hitting the shelves: Americans are headed into

another summer with new coronavirus variants and a likely uptick in

cases.

This is shaping up to be the first covid wave with barely any federal pressure to limit transmission and little data to even declare a surge. People are no longer advised to isolate for five days after testing positive. Free tests are hard to come by. Soon, uninsured people will no longer be able to get coronavirus vaccines free.

So we’re left with a virus that continues to hum in the background as

an ever-present pathogen and sporadic killer. The public health

establishment no longer treats covid as a top priority. Only a

smattering of passengers still wear masks on trains and planes.

Weddings, vacations and conferences carry on as normal. Many who do get

sick won’t ever know it’s covid. Or care.

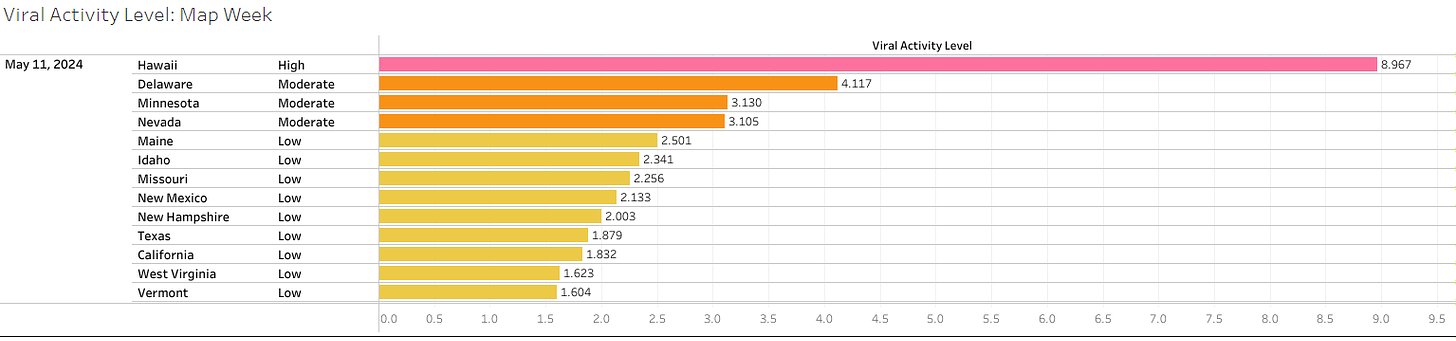

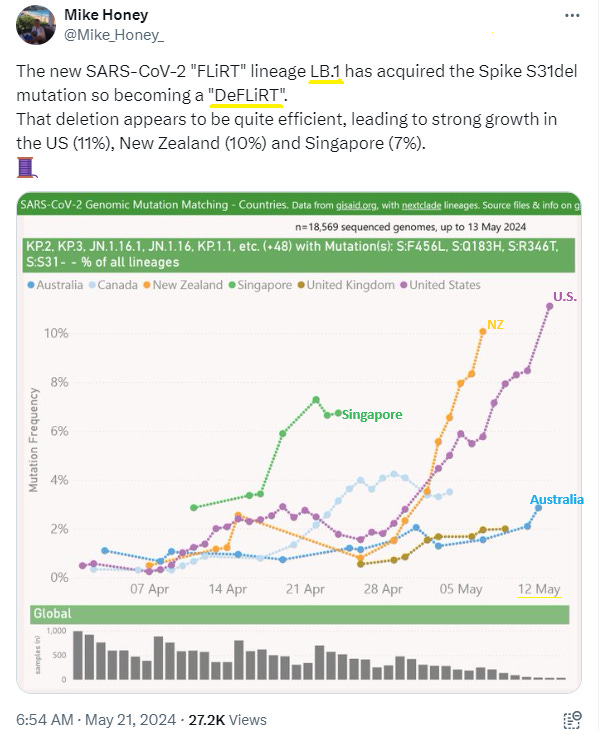

Covid returned to the headlines following the rise of new variants dubbed “FLiRT,”

far catchier than the JN.1 variant that drove the winter wave. Leading

the pack of those variants in the United States is KP.2, accounting for 28 percent of all infections

as of early May, according to the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. But public interest seems driven more by the name than the

biological features of the variants, which appear unremarkable beyond

the expected evolution of a virus to infect people more easily.

Summer offers a reminder of why covid is unlike the flu, a more

predictable fall and winter respiratory virus. Coronavirus ebbs and

flows throughout the year, and hospitalizations have always risen in summer months when people travel more and hot weather drives people indoors. For now, covid activity is low nationally, the CDC said Friday.

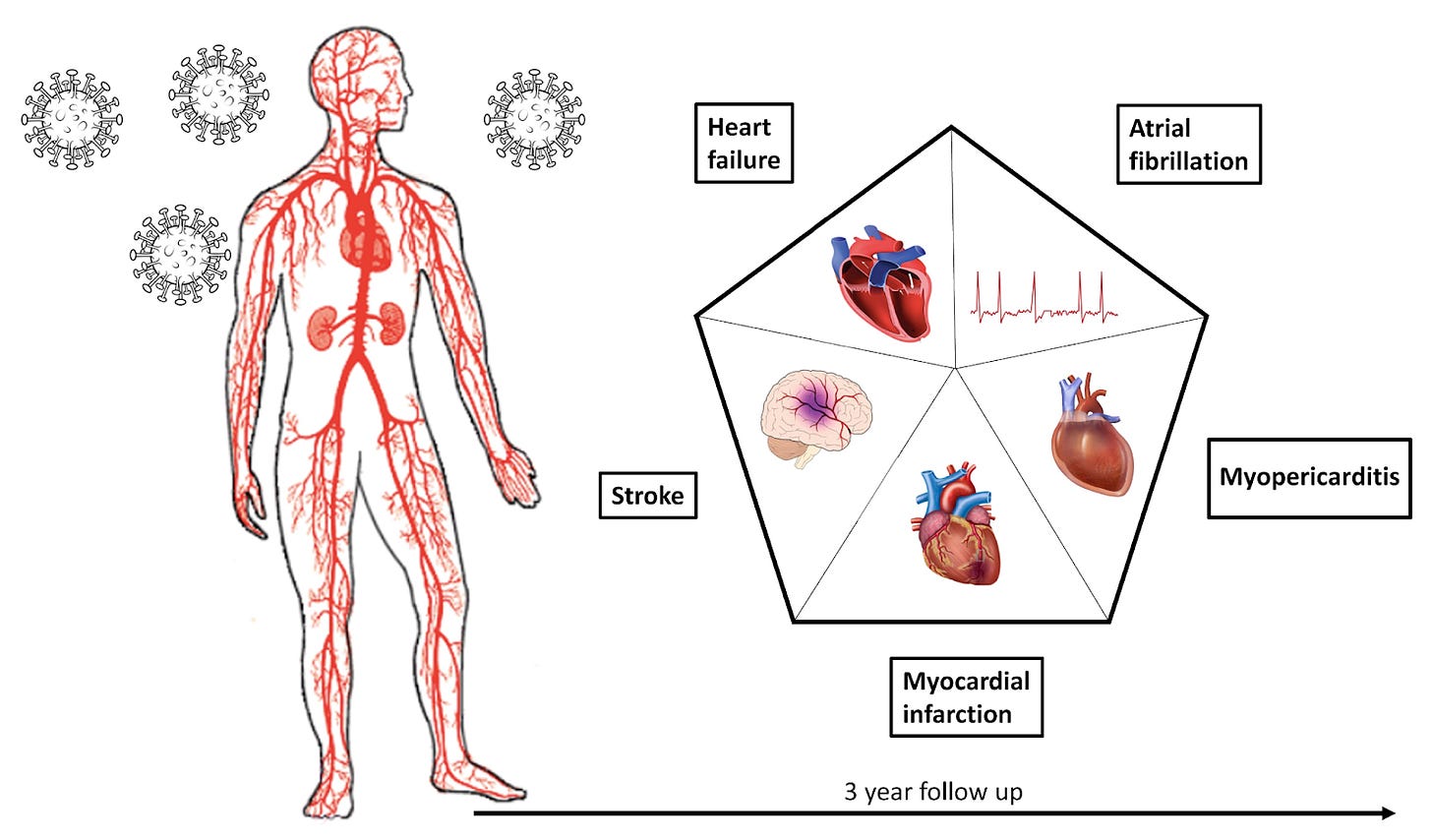

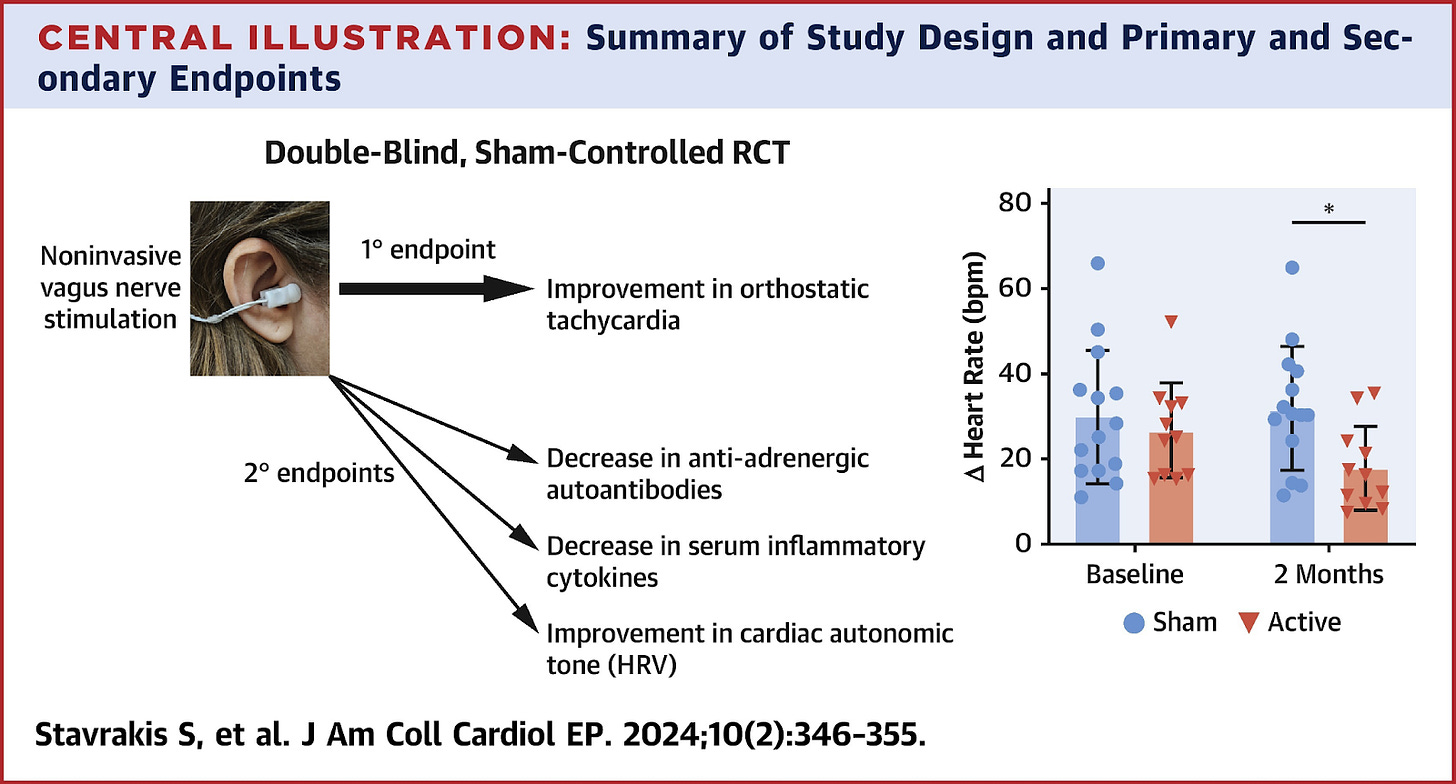

The number of Americans dying of covid is less than half what it was a

year ago, with a death toll around 2,000 in April. The virus poses a

graver threat to the severely immunocompromised and elderly. But it can

still surprise younger healthy people, for whom a bout of covid can

range from negligible sniffles to rarer long-term debilitating effects.

When Lauren Smith, a 46-year-old triathlete in New Jersey, got covid in

late April, she figured it would be a “nothingburger” like her first

case two summers ago. Instead, she said she developed persistent fatigue

for weeks that has made it difficult to train, and she decided to pull

out of her upcoming competition. Her case is one that doctors would call

mild, but Smith says doing so obscures the reality of a virus more

complicated than the flu.

“There’s no care or attention given to the fact that this is serious,”

said Smith, noting that she was one of the only masked attendees at a

recent Guster concert in Philadelphia. “I feel like so many people have

said, ‘I’m tired of this, I don’t want to deal with this anymore.’ And I

don’t feel like the CDC or any other agency is doing anything to combat

that.”

The Biden administration and the CDC don’t talk much about covid

anymore, save for sporadic updates on data and variant tracking, and the

president’s criticism, when campaigning, of his predecessor’s handling

of covid. CDC Director Mandy Cohen hasn’t tweeted about covid since

March. The agency declined to make an official available for an

interview about its response.

The CDC and health authorities continue to promote the coronavirus vaccine, last updated in fall 2023

for a subvariant no longer in circulation, as the best form of

protection against the disease. Just 23 percent of adults have received a

dose of the latest vaccine, the CDC estimates.

Experts say the existing formula should still confer protection against

severe illness from the FLiRT variants. People 65 and older qualify for

a second dose, but only 7 percent have received two shots.

Expert advisers to the Food and Drug Administration are scheduled in June to recommend the composition of the coronavirus vaccine to be released in the fall to protect against the latest variants.

But people without health insurance will no longer qualify for free vaccines under the CDC’s Bridge Access Program,

which ends in August after providing more than 1.4 million free shots.

Funding for the program ran out, and efforts to establish a broader

national program offering free vaccines for adults have languished.

Peter Hotez, co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for

Vaccine Development, said declining covid data collection will make it

harder to persuade Americans that the virus poses enough of a threat to

merit getting vaccinated.

In April, hospitals stopped reporting confirmed covid-19 cases — ending

the most commonly cited metric for measuring the virus’s toll. The CDC

still tracks the levels of coronavirus detected in wastewater and discloses the percentage of emergency room visits

with a diagnosed covid-19 case, which has been declining since

February. But Hotez said the available metrics are no longer enough to

properly grasp the covid situation.

“We’re kind of

shooting blind now,” said Hotez, who is also dean of the National School

of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine.

Public health officials treat covid with less urgency in part because

hospitals no longer report that covid patients pose a significant threat

to their capacity.

Raynard Washington,

who leads the Mecklenburg County health department in North Carolina,

noted that while covid remains deadlier and more transmissible than the

flu, the virus has become far more manageable because of vaccination.

“It’s not causing disruption to our everyday life like it used to,” Washington said

While health-care systems can manage covid waves, Otto Yang, associate

chief of infectious diseases at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine,

said the immunocompromised and older adults at high risk of developing

severe disease are often overlooked.

“Those people

unfortunately carry a heavy burden,” Yang said. “I’m not sure there is a

good solution for them, but one thing could be better preventive

measures.”

The

covid protection measures that were a staple of earlier summers —

requests to test before attending weddings, mask requirements at

conferences, outdoor locations for celebrations — are falling by the

wayside.

Many summer campers, for instance, will no longer be forced to isolate for covid while asymptomatic since the CDC revised its quarantine protocols to allow people to reemerge

after their fevers break, said Tom Rosenberg, president and chief

executive of the American Camp Association. But other covid protections

have stuck: Opening windows to improve ventilation, screening for

symptoms of illness and discouraging parents from helping their kids

unpack when they arrive. Regardless of the pandemic’s severity,

Rosenberg said, camps seek to minimize disruptions from illness.

“Kids can have more fun,” Rosenberg said. “We want to keep them in

camp as much as we can as long as they are well and ready to

participate.”

Others trying to keep precautions in place face greater challenges as they become outliers.

Organizers of Dyke Fest, an LGBTQ+ community gathering in D.C., wanted

to be inclusive of immunocompromised people when they asked attendees

to wear masks and test before coming to a bar where more than 250

attendees drank, browsed jewelry and art, and joined packed crowds

watching drag performances. But compliance was spotty and enforcement

tricky when rain drove people indoors, where drinking and masking don’t

easily mix, and pandemic masking norms have eroded.

“Culturally we are

coming away from it as a society, so it gets much harder to ask people

to really be consistent, because they aren’t doing it anywhere else,”

said D Schwartz, one of the organizers. “You go into a movie theater

now, you see maybe five people wearing a mask.”

Medically vulnerable people are adjusting to a world where they can’t count on people to mask anymore, even at the doctor’s office. In North Carolina, Republican lawmakers proposed legislation

in May that would criminalize mask-wearing in public, even for medical

reasons, in response to growing protests against the war in Gaza, where

many protesters have worn medical masks.

The proposal floored Cat Williams, who received a double lung transplant

and faces heightened danger from covid infections because she takes

medication that suppresses her immune system. At medical appointments,

she has had to plead with medical staff to cover their faces while she

gets her blood drawn and undergoes X-rays. The prospect of getting

arrested for wearing a mask and being forced to take it off in a crowded

jail makes her even more fearful to leave home. And she worries mask

skeptics will be emboldened to harass people who wear them.

“We have a target on our backs,” said Williams, 53, of Charlotte. “They

don’t want anyone to give them the reminder that covid is around.”

.jpg)