Here is

Dr Ruth Ann Crystal's latest newsletter, COVID & Health News, 4/27/25:

---------------------------

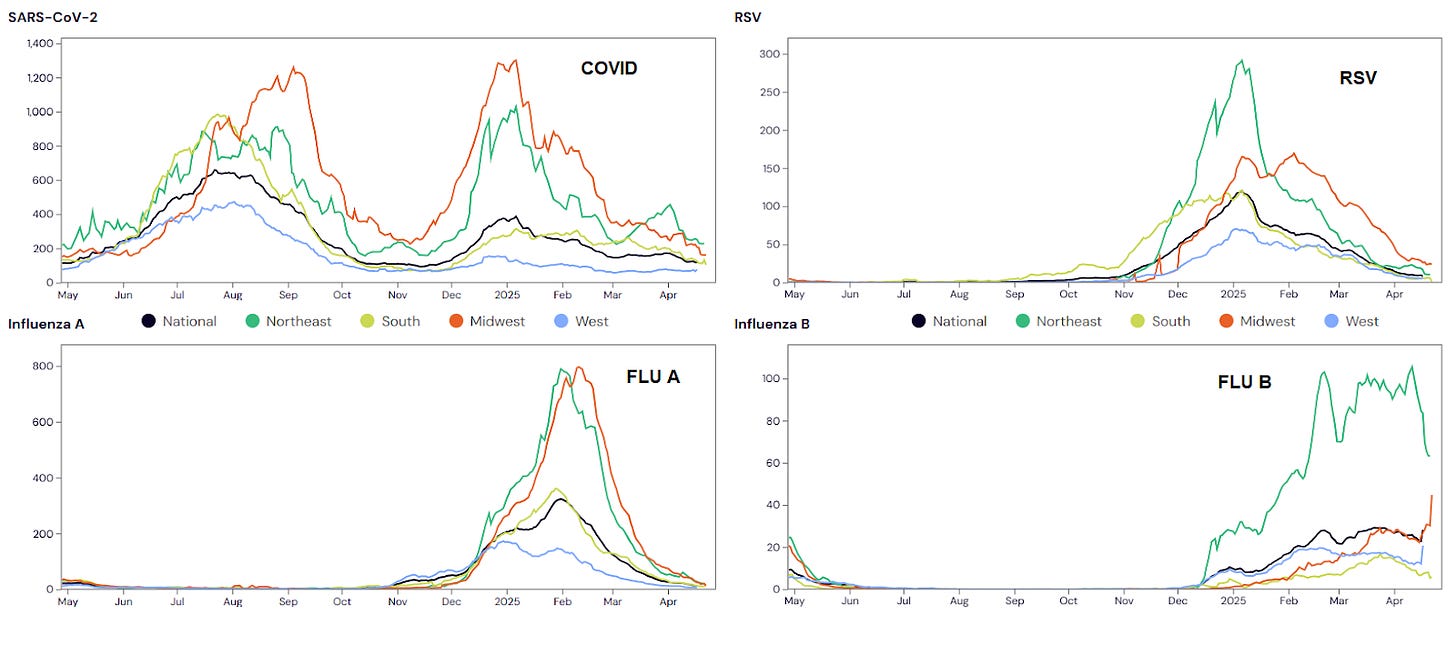

"This week, the CDC reports LOW overall levels of respiratory illness with COVID, RSV, and influenza hospitalizations are trending downward nationally. Influenza B remains more prevalent than Influenza A especially in the Northeast, but levels are decreasing.

COVID

"Wastewater monitoring from the CDC through 4/19/25 showed that most of the country was at low SARS-CoV-2 levels. As of 4/27/25, WastewaterSCAN shows LOW levels of SARS-CoV-2 across most of the U.S., though MEDIUM levels persist in the Midwest and HIGH levels in the Northeast. Fewer sites are high in the Northeast as compared to last week. Nationally, COVID transmission is declining but remains slightly higher than some past spring lows due to the muted winter surge, per JP Weiland.

"According to Michael Hoerger, about 1 in 196 people in the U.S. are actively infectious with COVID. The South has higher transmission (1 in 118) and Louisiana cases are high (1 in 63). In contrast, the West has lower levels (1 in 240). Emergency department visits and deaths from COVID remain low, and weekly deaths are nearing record lows this spring.

"In California, most regions report LOW wastewater levels for COVID, though Novato is still HIGH per WastewaterSCAN. CDPH's wastewater data have not been updated since 4/10/25.

Variants

"LP.8.1 represents 69% of COVID cases now and XEC is down to 10%.

Acute COVID infections, General COVID info

"This week, the White House deleted health information about COVID testing, treatment, and vaccination, as well as information on Long COVID from the COVID.gov website, replacing it with a lab leak theory featuring a photo of Donald Trump.

Pediatrics

"Children who tested positive for COVID face significantly higher long-term risks for chronic kidney disease, gastrointestinal disorders, and cardiovascular issues

compared to peers who tested negative. The study, led by the University

of Pennsylvania and part of the NIH’s RECOVER initiative, found kidney

disease risks increased up to 35%, GI symptoms by up to 28%, and

cardiovascular conditions like heart inflammation or arrhythmias by 63%.

Racial differences also emerged with Asian American Pacific Islander

children showing slightly higher Long COVID risk.

“While

most public attention has focused on the acute phase of COVID-19, our

findings reveal children face significant long-term health risks that

clinicians need to monitor,” said senior author Yong Chen, PhD.

"Another study from the University of Pennsylvania found that unvaccinated children and adolescents were up to 20 times more likely to develop Long COVID

than those who were vaccinated. The vaccine’s protection against Long

COVID comes mostly from preventing infection rather than reducing risk

after infection.

"A nationwide study in Israel tracked 101,626 five-year-old kindergarteners over a decade and found that myopia (nearsightedness) prevalence nearly tripled

from 3.7% to 12.6% following COVID lockdowns. Researchers linked this

increase to less outdoor time and more screen use which are known risk

factors for myopia.

"Using mass spectrometry and a

machine learning technique called support vector machine (SVM) to find

protein patterns in blood samples, a group from Rutgers found protein

signatures that can distinguish children with Multisystem Inflammatory

Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) from those with acute COVID infection,

pneumonia, or Kawasaki disease. In MIS-C, proteins related to

inflammation and clotting increased, while those tied to lipid

metabolism decreased. A three-protein model (ORM1, AZGP1, SERPINA3)

distinguished MIS-C from mild COVID-19 with high accuracy (up to 93.5%

AUC), and another three-protein signature (VWF, SERPINA3, FCGBP)

successfully separated MIS-C from other febrile illnesses like pneumonia

and Kawasaki disease.

Share

Vaccines

"Amid rising measles cases, vaccine misinformation, and public health funding cuts, CIDRAP has launched the Vaccine Integrity Project

to promote evidence-based vaccine use in the United States. Funded by a

$240,000 gift from the Alumbra Foundation, the project will evaluate

how non-governmental groups can help ensure vaccine safety and

effectiveness remain grounded in science.

“This

project acknowledges the unfortunate reality that the system that we've

relied on to make vaccine recommendations and to review safety and

effectiveness data faces threats.” Michael Osterholm, PhD, MPH

"The FDA has requested that Novavax complete a new randomized clinical trial for its COVID vaccine creating costly hurdles

that could delay U.S. approval. Novavax has already shown 90% efficacy

and is approved abroad. This move, influenced by officials under Health

Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., has raised concerns about political

interference in vaccine approvals.

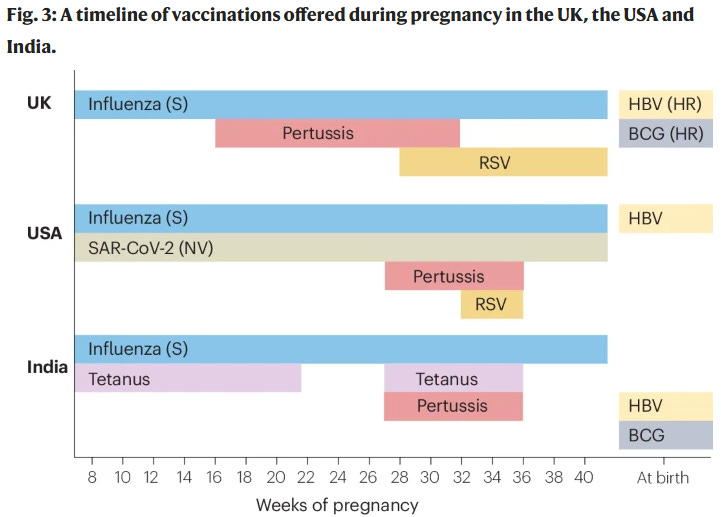

"This week, there was a review in Nature on vaccination in pregnancy

as an important way to protect newborns from infections. Since newborns

have immature immune systems and limited vaccine options, maternal

antibodies passed through the placenta offer crucial early protection.

The article highlights successful examples like vaccines for tetanus,

pertussis, influenza, and COVID-19, and notes recent approvals for

respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines and upcoming vaccines for

Group B Streptococcus.

Antiviral treatments

"A

group from Istanbul tested drugs that are already FDA-approved for

other indications to see which could inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 3CL

protease. Lumacaftor, candesartan, nelfinavir and other drugs showed strong antiviral activity against COVID replication in vitro. Clinical trials will be needed to see if these drugs could be repurposed to treat COVID.

"A

large U.S. EMR-based study found that taking Paxlovid within 5 days of a

mild-to-moderate COVID-19 diagnosis significantly lowered the risk of

stroke and death 90+ days later. Among nearly 182,000 matched patient

pairs, those who took Paxlovid had a 15% lower risk of stroke and a 32% lower risk of death.

The benefit was consistent across all age groups, sexes, health

conditions, and vaccination statuses, with particularly strong

protection seen in older adults and those with obesity or metabolic

diseases.

Long COVID

"A

new study using specimens from the UCSF LIINC biobank found that people

who had COVID, and especially those with Long COVID, showed signs of

persistent immune dysfunction and metabolic imbalances up to four months

after infection. Those with Long

COVID had immature, inflamed immune cells, high oxidative stress, low

tryptophan levels, and markers of immune cell exhaustion and senescence

especially in CD8 T-cells. The researchers also identified changes in gene methylation linked to disrupted metabolism and potential cancer risk,

suggesting that Long COVID may result from long-lasting damage to

immune and metabolic systems. Other viruses like Epstein Barr Virus

(EBV) and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) are known to cause cancers, and

SARS-CoV-2 may have oncogenic potential as well.

"Another study showed that mild or asymptomatic COVID infections can cause long lasting changes to DNA methylation patterns seven months after infection. Two specific DNA sites on AFAP1L2 and PC

genes which are linked to immune responses and how cells use energy,

were consistently altered. Changes resembled patterns seen in autoimmune

or inflammatory diseases suggesting long-term epigenetic remodeling

even after mild COVID infection.

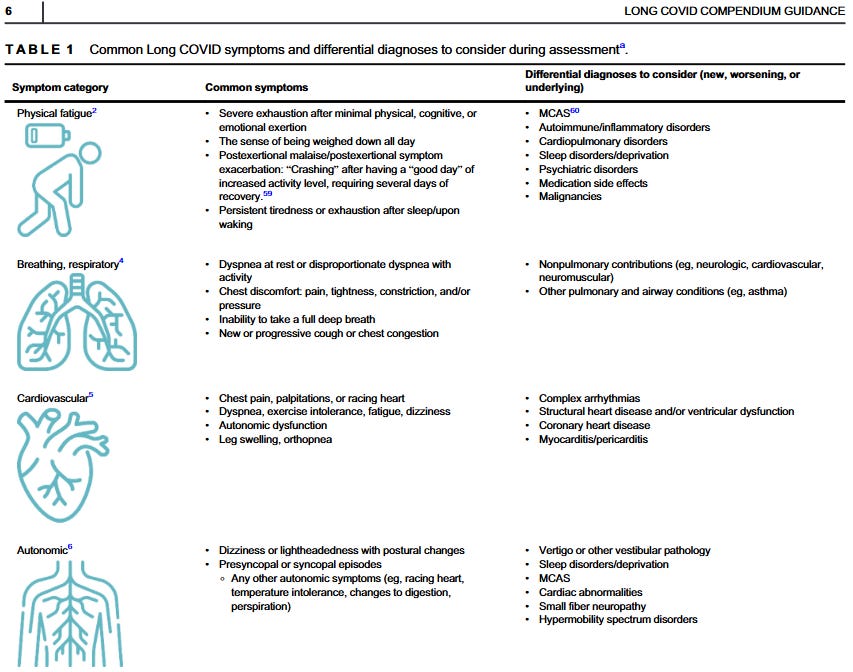

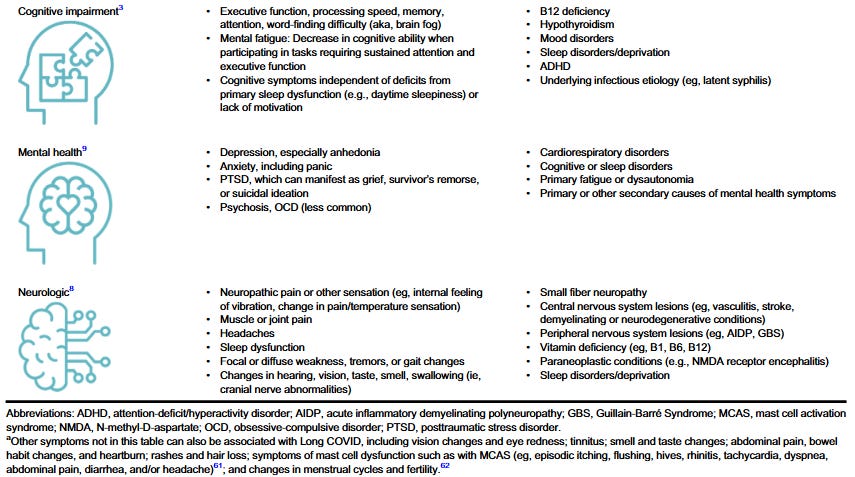

"Long COVID affects

over 400 million people worldwide, yet there is little guidance or

formal training for healthcare professionals. This week, two different

groups put out amazing articles on the diagnosis and treatment of Long

COVID with helpful tables. The first paper

was published by a multidisciplinary group associated with the American

Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (AAPM&R)

Multidisciplinary PASC Collaborative and the other paper was written by 179 global Long COVID experts, both using a Delphi approach.

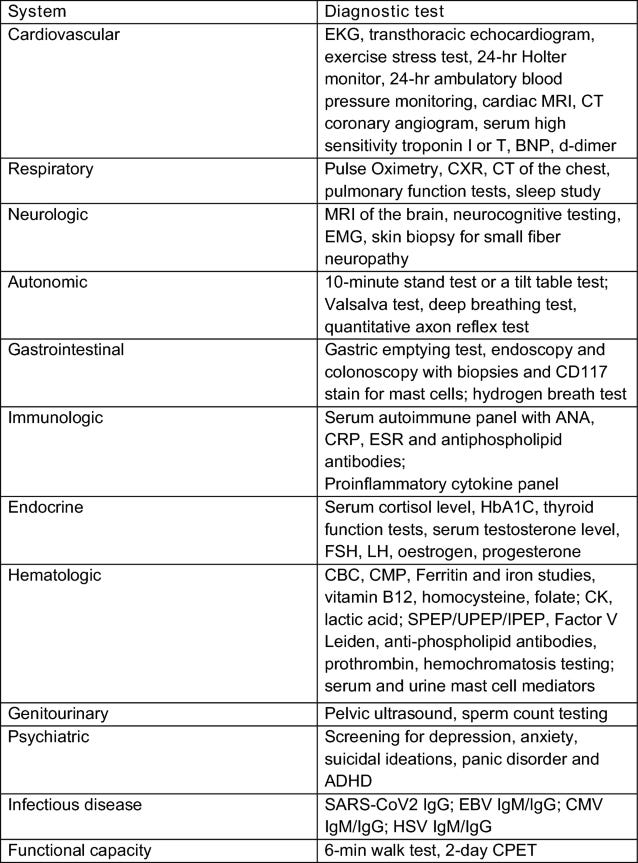

"The AAPM&R Multidisciplinary PASC Collaborative wrote an extensive compendium on the differential diagnosis, testing, management and treatment of Long COVID broken down by symptom. I found this article to be extremely helpful and very detailed.

"The second paper entitled “Long COVID clinical evaluation, research and impact on society”

was written by 179 international experts on Long COVID who used a

3-round Delphi method to build consensus on key recommendations for

definition, diagnosis, treatment, research, and societal issues relating

to Long COVID.

"Table 3 Recommended diagnostic tests

available to clinicians for evaluation of patients with Long COVID based

on clinical history and examination

"Western

University in Canada and the Schmidt Initiative for Long COVID (SILC)

have launched a global clinical trial to evaluate two repurposed

anti-inflammatory drugs upadacitinib and pirfenidone as potential treatments for Long COVID. The trial will enroll 348 participants across seven sites on four continents, using an adaptive trial platform

to focus on the most severe symptoms in each patient, including

fatigue, brain fog, breathing issues, and muscle aches. The two drugs

were selected using artificial intelligence (AI) from over 5,400

proteins linked to Long COVID, offering a promising shortcut to

treatment by targeting 13 shared biological pathways.

"A new preprint validated earlier findings that genetic factors strongly influence who develops Long COVID,

using data from both U.S. (All of Us) and U.K. (Sano GOLD) cohorts with

diverse ancestries. Over 90% of genes identified in the original study

were also associated with Long COVID in the U.S. population including in

Black and Hispanic groups. These results confirm that combinatorial

genetic analysis can uncover more risk genes than traditional

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and support the continued

exploration of drug repurposing candidates for Long COVID treatment.

"A

study in BMJ Global Health of 6528 adult patients with symptomatic

COVID from Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Egypt, India,

Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and the

United Arab Emirates found that 25% of COVID patients reported Long COVID symptoms with higher rates in less wealthy countries and among people of Arab or North African ethnicity.

Share

Lyme Disease

"New research from Northwestern University suggests that lingering symptoms after Lyme disease treatment may be driven by immune responses to leftover bacterial cell wall fragments called peptidoglycans

and not active infection. Scientists found that B. burgdorferi

peptidoglycan persists in the liver and joints long after the bacteria

are killed. These remnants appear to trigger prolonged inflammation in

some patients, much like viral fragment persistence may trigger

inflammation in Long COVID. This may explain why anti-inflammatory drugs

can sometimes help Lyme disease symptoms when antibiotics do not. The

group also showed that B. burgdorferi peptidoglycan alters energy

metabolism in immune cells and triggers protein changes similar to those

seen in chronic illness after infection.

"Researchers from Virginia Tech screened 500 antibiotics and identified that piperacillin may be a potentially safer alternative to doxycycline for treating Lyme disease.

These findings could lead to better treatments and more targeted

therapies for the roughly 1,200 people diagnosed with Lyme disease each day in the United States.

ME/CFS

"Researchers

used deep learning techniques to analyze genetic data from individuals

with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). HEAL2,

a novel deep learning framework, identified 115 ME/CFS risk genes

that show mutations in the central nervous system (CNS) and immune

cells. Further analysis of these ME/CFS genes shows a “genetic

correlation between ME/CFS and other complex diseases and traits,

including depression and Long COVID.”

H5N1

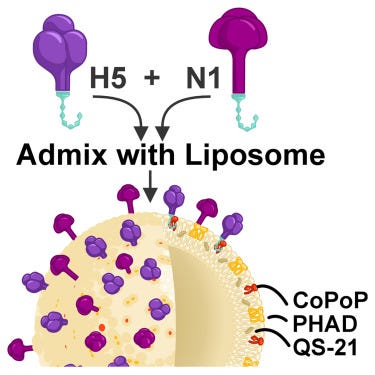

"A group from SUNY Buffalo developed a nanoparticle vaccine candidate

that displays recombinant H5 and N1 proteins from the highly pathogenic

avian influenza H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b on liposomes. In mice, this vaccine

triggered strong immune responses and protected against lethal

infection showing promise for future pandemic preparedness. The vaccine

will be developed for potential use in both animals and humans.

Graphical Abstract

Measles

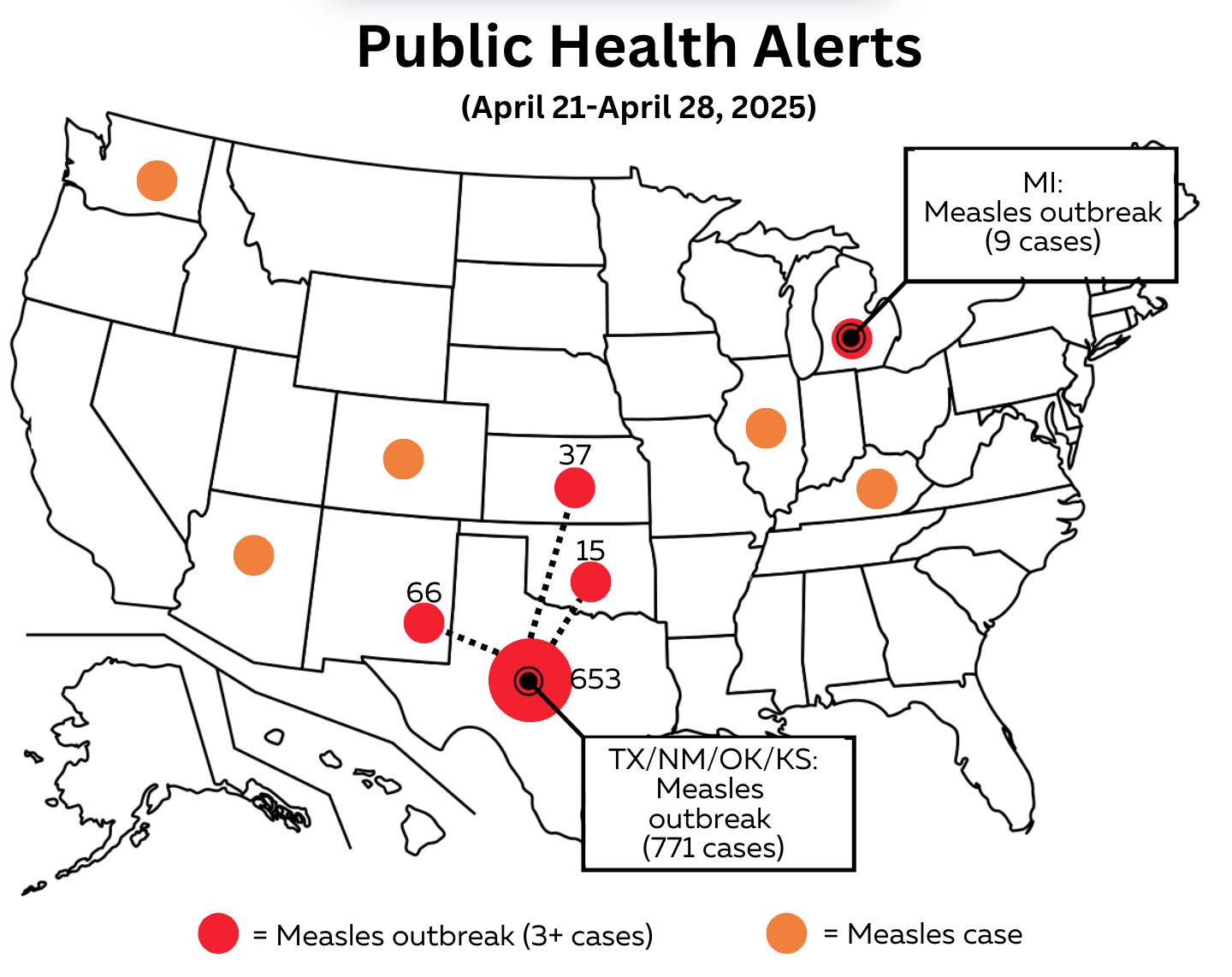

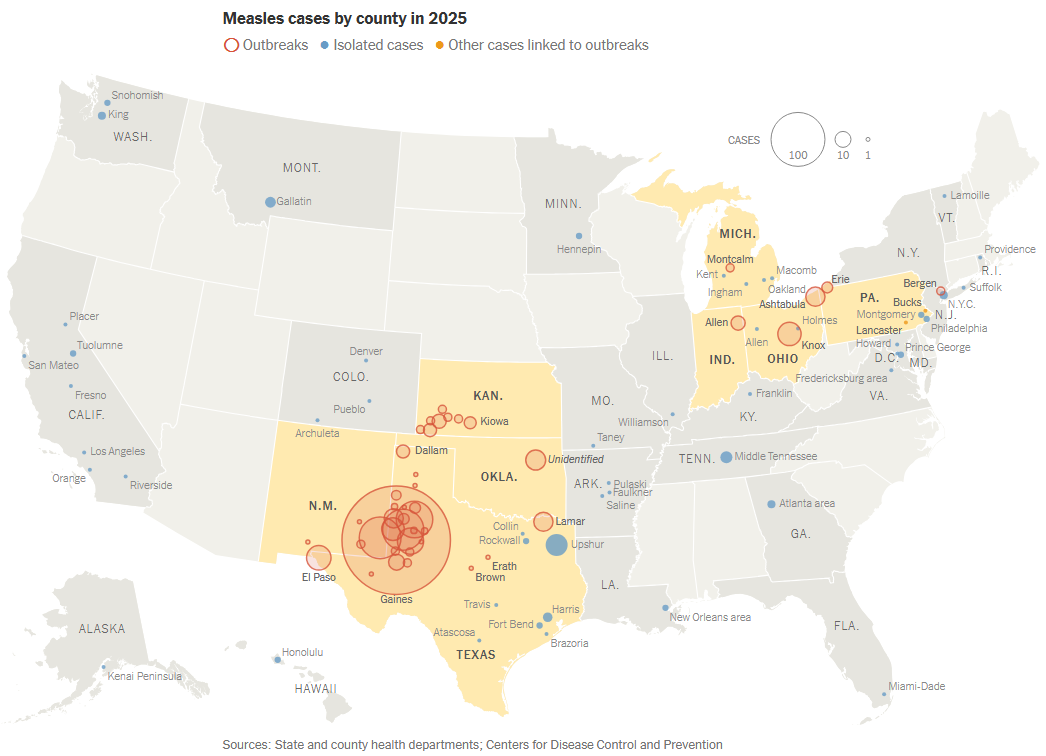

"As of 4/24/25, the CDC reports 884 reported US measles cases

in 2025 with 11% hospitalization for pneumonia and other complications

and 3 reported deaths. Measles have been reported in 29 states now.

"A

new simulation study from Stanford warns that declining childhood

vaccination rates in the United States could lead to a resurgence of

previously eliminated diseases like measles, rubella, polio, and

diphtheria. Even if we stay at current vaccination rates, measles could become endemic again within 21 years, underscoring the urgent need for high vaccine coverage to prevent major public health setbacks.

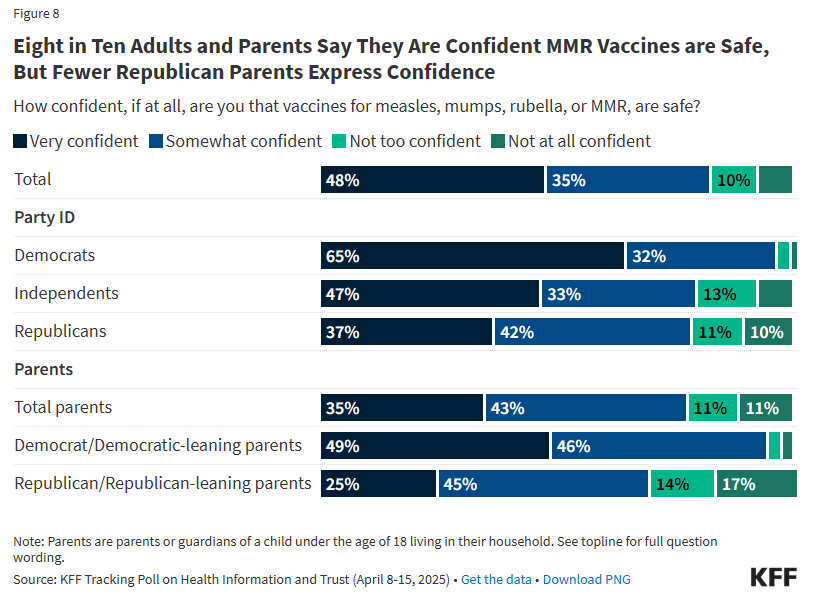

"As

measles cases surge to the highest levels since 2019, about half of

adults and parents are worried, with concern higher among Black,

Hispanic, and Democratic respondents per a new KFF poll.

Many adults have encountered false claims about measles and MMR

vaccines, but overall 83% still express confidence in vaccine safety.

Partisan divides strongly influence both awareness of the measles

outbreak and belief in vaccine misinformation.

Share

Other news

Multiple Sclerosis and Gut Microbiota

"Taking

gut bacteria from an identical twin with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and

putting it in the gut of germ-free mice triggered MS-like disease in the

mice, suggesting a causal role for specific microbes. Implicated bacteria include Eisenbergiella tayi and Lachnoclostridium.

"Metformin may prevent a form of acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

in people at high risk of the disease. A common mutation in the DNMT3A

(R882) gene increases the risk of this leukemia. The mutated cells rely

heavily on mitochondrial energy production (OXPHOS). Using mouse models

and human data, a study showed that targeting this energy pathway with

Metformin can suppress the expansion of leukemia cells like AML.

"A Danish twin study found that tattoo ink exposure is linked to a higher risk of skin cancer and lymphoma,

especially with large tattoos. Individual-level analyses showed hazard

ratios up to 3.91 for skin cancer and 2.73 for lymphoma, with tattoos

larger than the palm of a hand carrying the greatest risk. The studies

were small and larger studies over a longer period of time will be

important to clarify health impacts of tattoo ink.

From ChatGPT

"For the first time, microplastics have been detected in human ovarian follicular fluid

raising concerns about potential impacts on female fertility. The study

found microplastics in 14 out of 18 women undergoing fertility

treatments suggesting widespread exposure. Researchers call for further

investigation into how these particles affect reproductive health.

"The FDA has suspended milk quality testing due to layoffs of FDA inspectors. Layoffs included FDA staffers responsible for responding to the ongoing bird flu outbreaks as well.

"The Trump administration ended federal funding for the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), a landmark study tracking the health of over 160,000 women since the 1990s. Thankfully, a day later, the administration restored funding to the WHI.

"When Serendipity Books

in Michigan needed to move to a nearby larger store, owner Michelle

Tuplin enlisted 350 local people who made two human chains and passed

each book down the line to the new store's bookshelves. The entire store

was moved within 2 hours and people had a great time discussing which

of the books they enjoyed.

People help move books for Serendipity Books. Photo by Burrill Strong from https://buff.ly/aUgRSBc

"Have a good week,

"Ruth Ann Crystal MD"

.jpg)