By Katelyn Jetelina and Hannah Totte, MPH, at Your Local Epidemiologist: The Dose, 2-3-26

As many of you are shoveling yourselves out of the snow, there is a lot happening in infectious diseases. Measles blew January out of the water, Nipah virus (yes, the virus that inspired the movie Contagion) is making headlines, and flu and RSV are still lingering.

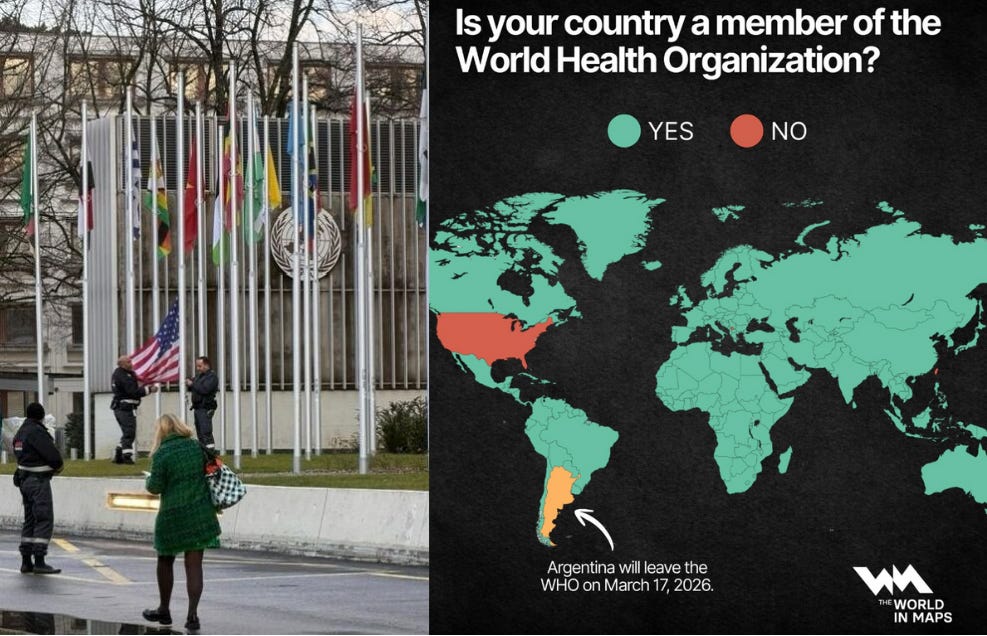

Meanwhile, the U.S. officially left the WHO, which seems… poorly timed, to say the least. A heartbreaking photo marks the moment and stands in stark contrast to the pride I felt when I worked at WHO ten years ago.

What does this all mean for you? Let’s dig in.

Measles: the first crack in childhood disease protection

We are watching the first building block of childhood disease protection fall in real time: protection against measles. Because this is the most contagious virus on Earth, even small drops in vaccination coverage give it an opening. And boy, are we giving it openings both nationally and globally.

What’s happening globally. On January 23, 2026, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced six European countries lost their measles elimination status: Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Uzbekistan. Canada lost its elimination status late last year. This means measles is no longer a random event in these countries; it’s endemic and freely flowing.

This is due to several forces colliding:

Collective amnesia about vaccine-preventable diseases (vaccines are victims of their own success)

Global instability

A radically changed online information ecosystem

Bad actors exploiting spaces

Deepening mistrust in institutions

WHO will examine the U.S. measles elimination status in April, and all signs point toward us losing it.

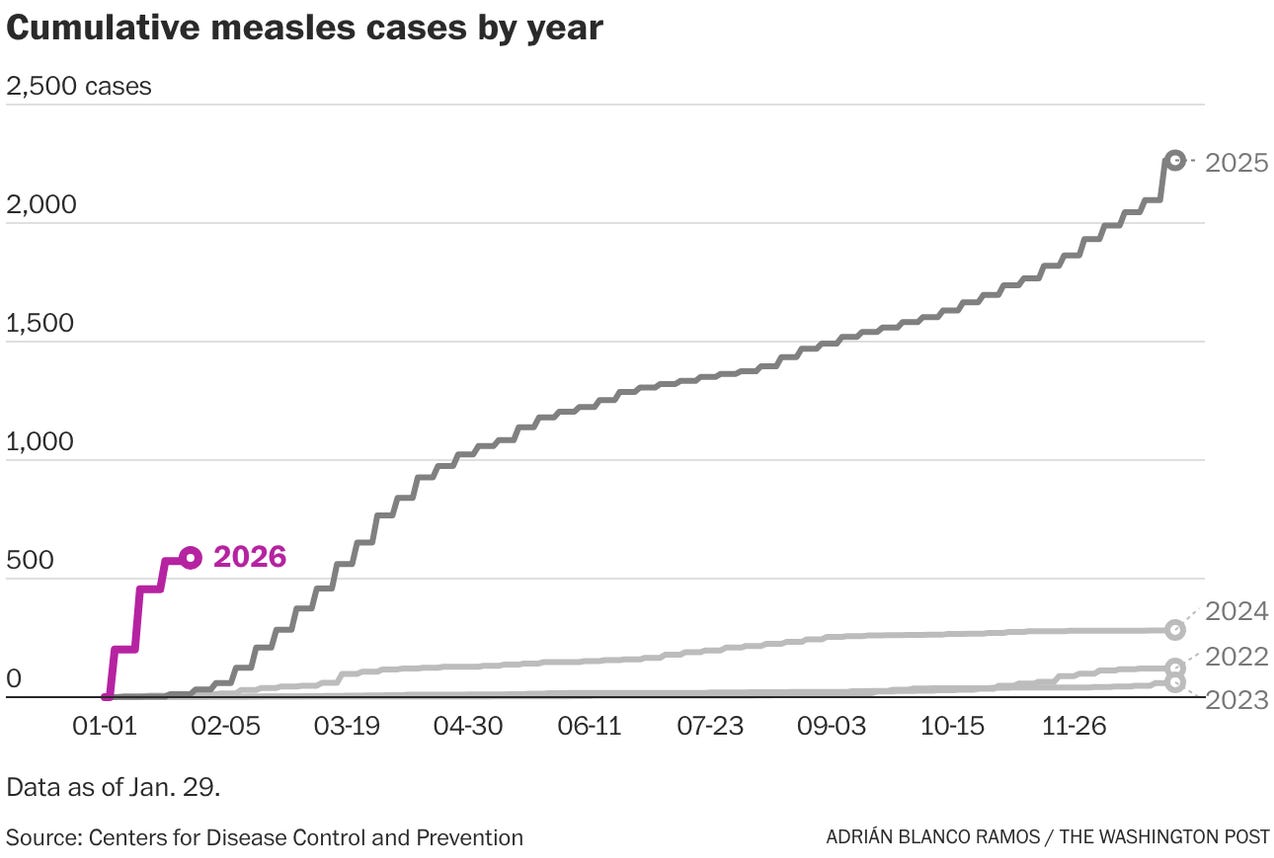

What’s happening in the U.S. This year isn’t off to a great start. In January 2026 alone, 662 measles cases were reported. This is an astonishing number for a single month. It’s especially concerning because January is typically a slower month for measles spread.

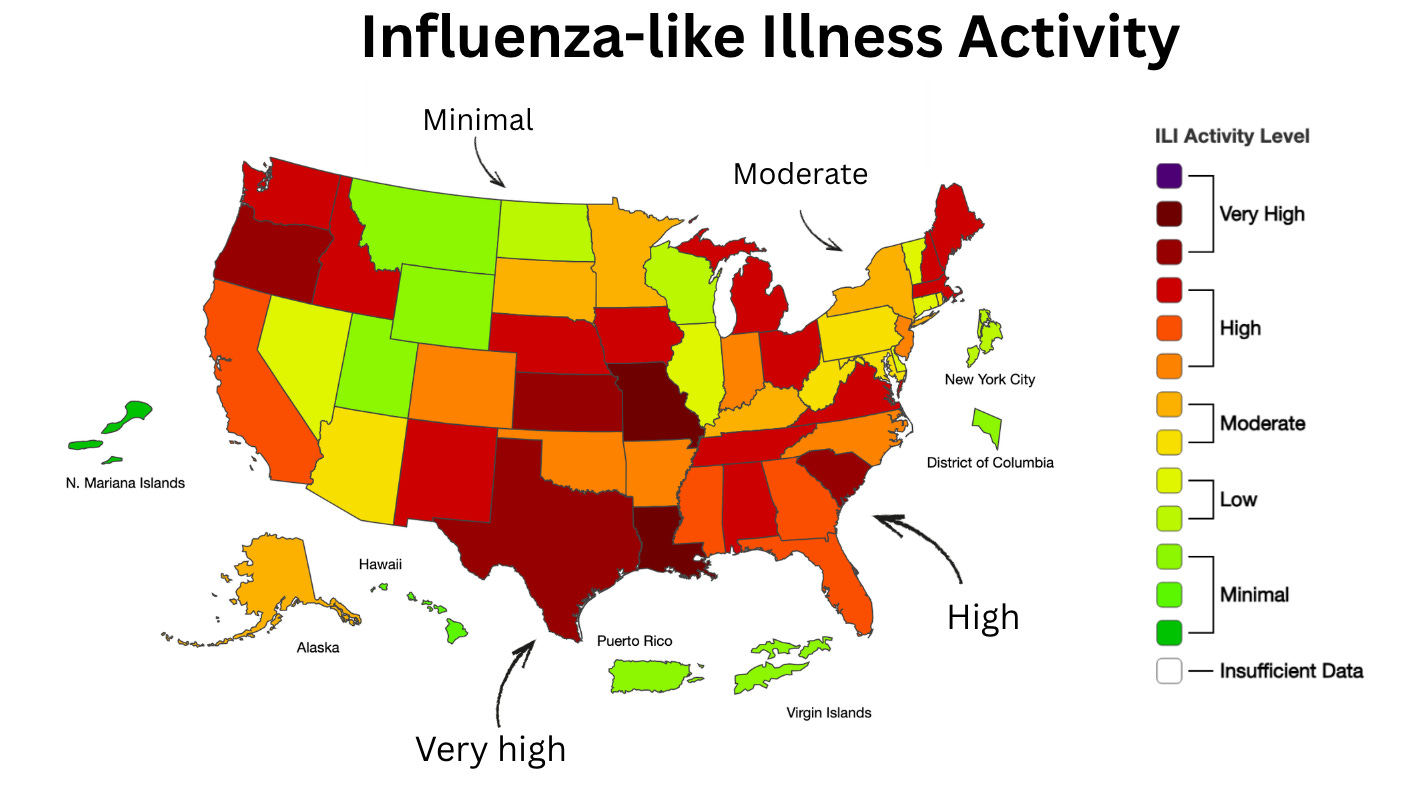

Public health eyes are on several areas:

South Carolina, where a large outbreak has surpassed the size of Texas’s outbreak last year, and is spreading through a tightly knit religious community with low vaccination rates. Wastewater is showing some hopeful signs that the outbreak may be slowing down.

Utah and Arizona, where cases continue to raise concern.

ICE detention centers in Arizona and Texas are reporting cases. This is concerning because these facilities have close quarters, making them a perfect breeding ground for measles.

What’s most troubling, in all of this, is the silence from national leadership. In the past, federal health leaders publicly encouraged vaccination and ran national prevention campaigns. Right now, that messaging is absent. Awareness, education, and empowerment are not front and center. As a result, measles will likely demand far more public health attention in the years ahead.

What this means for you: If you’re vaccinated, you’re very well protected. About 96% of cases are among unvaccinated people. Check vaccination rates in your county using this map. If you have a child under 12 months old, an early first MMR dose at 6 months may be an option. Talk with your pediatrician.

Nipah virus: scary headlines, low risk

Do you remember the movie Contagion? That fictional outbreak was inspired by Nipah, a serious virus that can cause brain swelling and has a high fatality rate (40-75%). There’s no approved treatment yet, though vaccines are in development, including one in clinical trials at Oxford. Vaccine progress in the U.S. has largely stopped due to vaccine skepticism and regulatory headwinds.

Right now, Nipah is causing a small outbreak in India. Social media and international headlines are lighting up, but we are not on the brink of another pandemic.

Here’s why.

The outbreak is small and controlled. This means the immediate risk is limited. Two nurses were infected in West Bengal. Indian health officials rapidly traced 196 contacts. All were quarantined, asymptomatic, and tested negative. This means the outbreak is under control. Some airports have added screening measures, despite no cases outside India, which appears to be an abundance of caution and possibly a reaction to exaggerated reports.

Nipah does not spread easily between people. Infected people become very sick very quickly, often dying, which limits opportunities for the virus to move to others. Nipah spreads through direct contact with bodily fluids, like blood, or contaminated food, but not through the air. As a result, one person with Nipah typically infects fewer than one other person. Compare that to measles, which can infect about 18 unvaccinated people from a single case. In short, human-to-human transmission is extremely limited.

Nipah primarily lives in animals. Fruit bats are the virus’s natural host, where it thrives. Occasionally, the virus jumps from bats to humans, particularly as deforestation, globalization, and climate change drive ecosystem changes. These spillover events are rare, and the virus does not easily spread from person to person.

Nipah poses a serious but highly localized risk rather than a global pandemic threat. While it could mutate, the risk of a pandemic is very, very small (about 2%).

What this means for you: Epidemiologists are keeping a close eye on this, and India has moved fast on containment. For now, Nipah still makes a great movie, but your risk is essentially zero.

Respiratory viruses: resurging

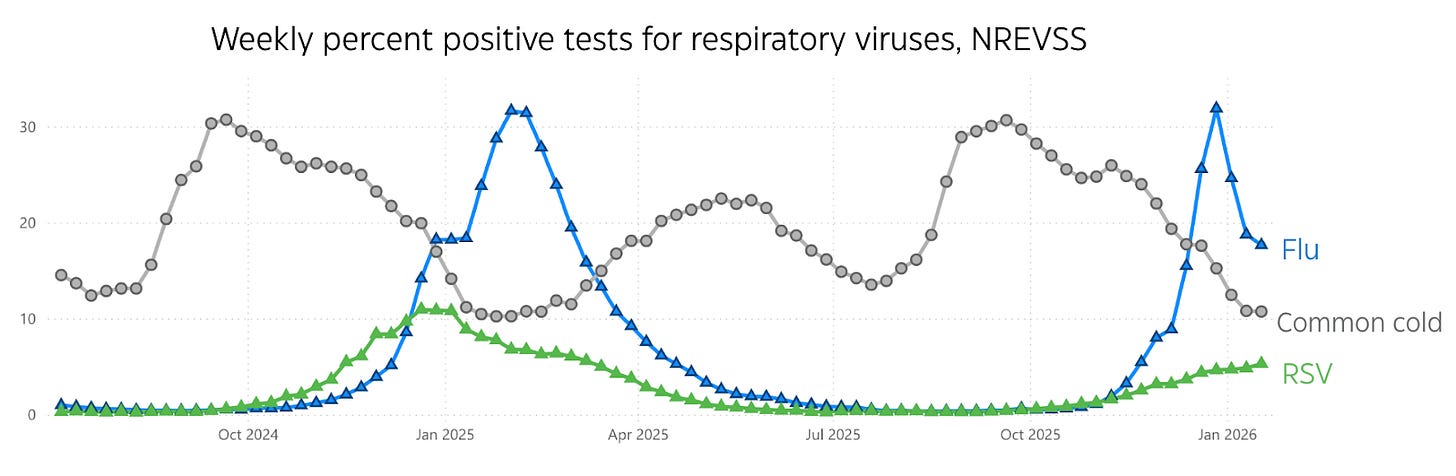

Reports of fever, cough, and sore throat are rising again, as is typical when schools resume after the holidays.

This increase is mostly driven by flu, especially among children. RSV is also contributing.

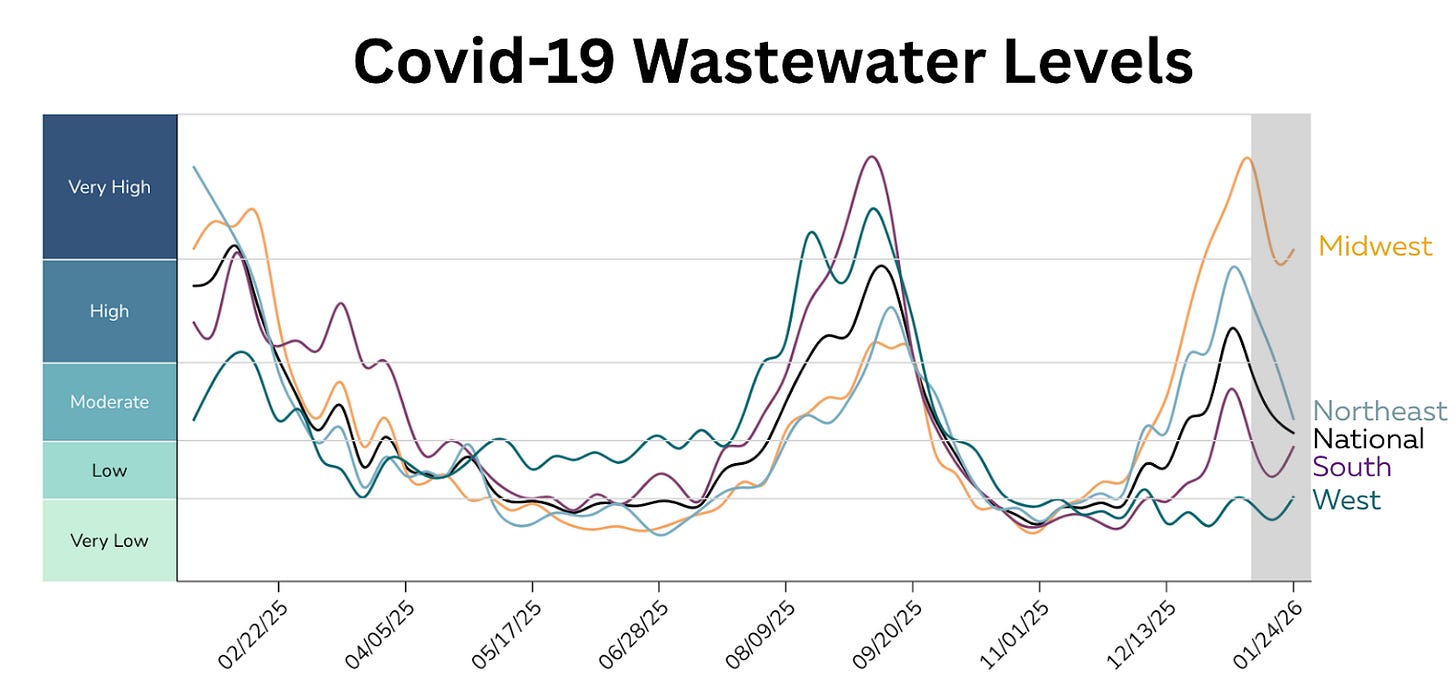

Covid-19 levels continue to drop nationally. While they remain highest in the Midwest, there might be increasing activity in the South. We will see where this virus takes us next.

What this means for you: At this point, it probably doesn’t make sense to get a flu vaccine until next season. Covid-19 vaccines for spring should be coming soon for those over 65 years old.

The U.S. officially leaves the WHO

More than ten years ago, I checked into the WHO headquarters in Geneva and took the picture below of all the UN flags—pride oozing from my veins as I worked toward a healthier world with all countries. Last week, I was sent a starkly different image: the U.S. flag being lowered at the WHO as the U.S. officially departed.

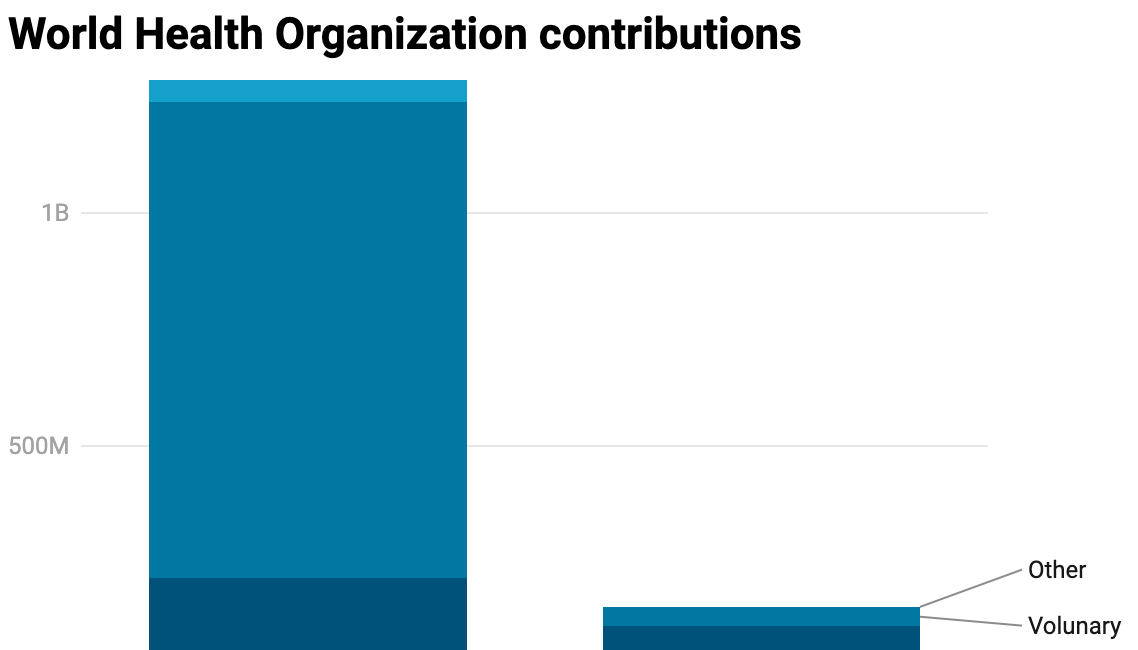

WHO has long needed support and reform; there’s no question about that. But reforming is very different from walking away, and it’s worth the effort. While this move may not directly affect all of us in the short term, the consequences are real: reduced financial support for low-income countries facing outbreaks like Nipah, diminished U.S. influence on the global stage, and Americans themselves becoming less informed and less prepared.

I wrote about this when the president first announced the plan to leave WHO, and the implications haven’t changed. Read more here:

The U.S. withdrawal from the WHO

More than 10 years ago, I moved to Geneva to work at the World Health Organization (WHO). I was a bright-eyed young epidemiologist with one mission: change the world! My job was admittedly unglamorous: sit in front of Excel, analyze HIV/AIDS drug prices across countries, and write a grueling report for each. and. every. country.

Did California join the WHO? Not exactly. States can’t be full members. But after the U.S. withdrawal, the California Department of Public Health began joining WHO weekly calls through the Global Outbreak Alert & Response Network, and other states will likely follow. This keeps states connected to critical information on global outbreaks and their potential impact on Americans, now that the CDC is no longer filling this role.

What this means for you: Health threats don’t respect borders. This will make it much harder for public health to protect you.

Bottom line

Infectious diseases love this time of year, and this week is no exception. I hope you all stay healthy, safe, and warm out there.

Love, YLE

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. Hannah Totte, MPH, is an epidemiologist and YLE Community Manager. YLE reaches more than 425,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “Translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment