YLE Public Health Emergencies: Covid still high, mpox emergency, and parvovirus enters the chat

Lots is happening in the public health world! Here’s your latest update.

Covid-19: Very high

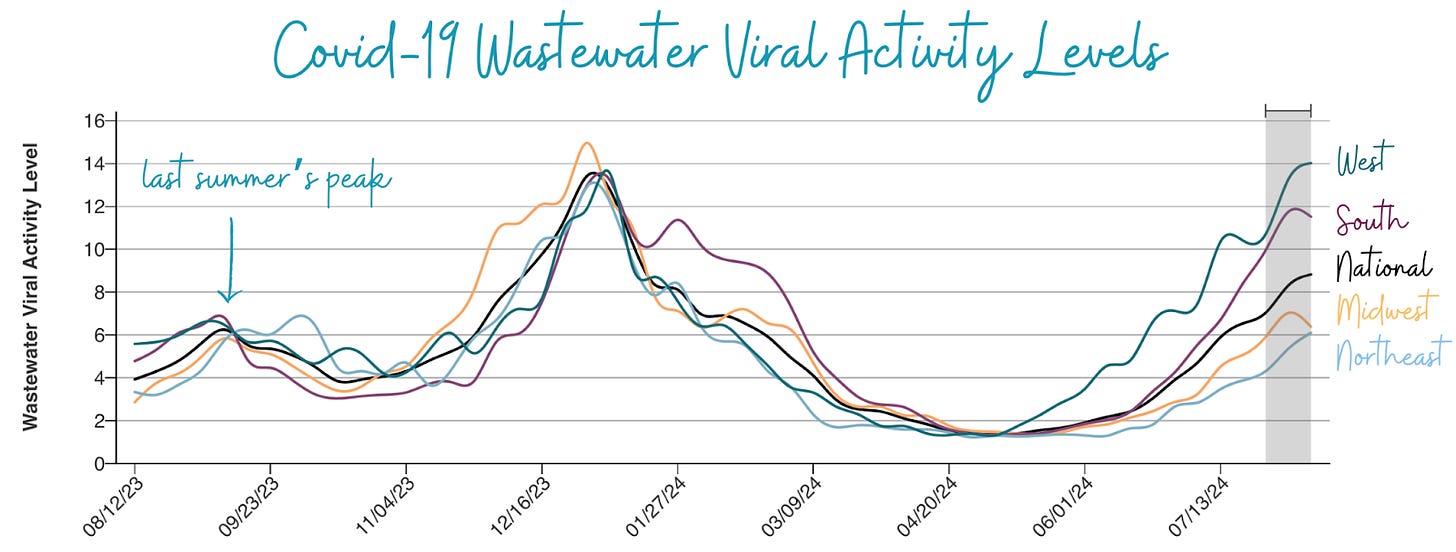

Viral activity in wastewater—our best indicator of Covid–19 spread—is still “very high,” marking a very impressive summer wave. In fact, levels in the West are now the worst on record since the Omicron tsunami in 2021.

There are signs of declining rates in the South and Midwest and a plateau in the West. However, recent wastewater signals can be unstable (look at that rollercoaster in the West below), so I’m not getting too excited yet.

In addition, we are getting mixed signals from other metrics. Emergency department visits have shown signs of slowing down, but test positivity hasn’t yet.

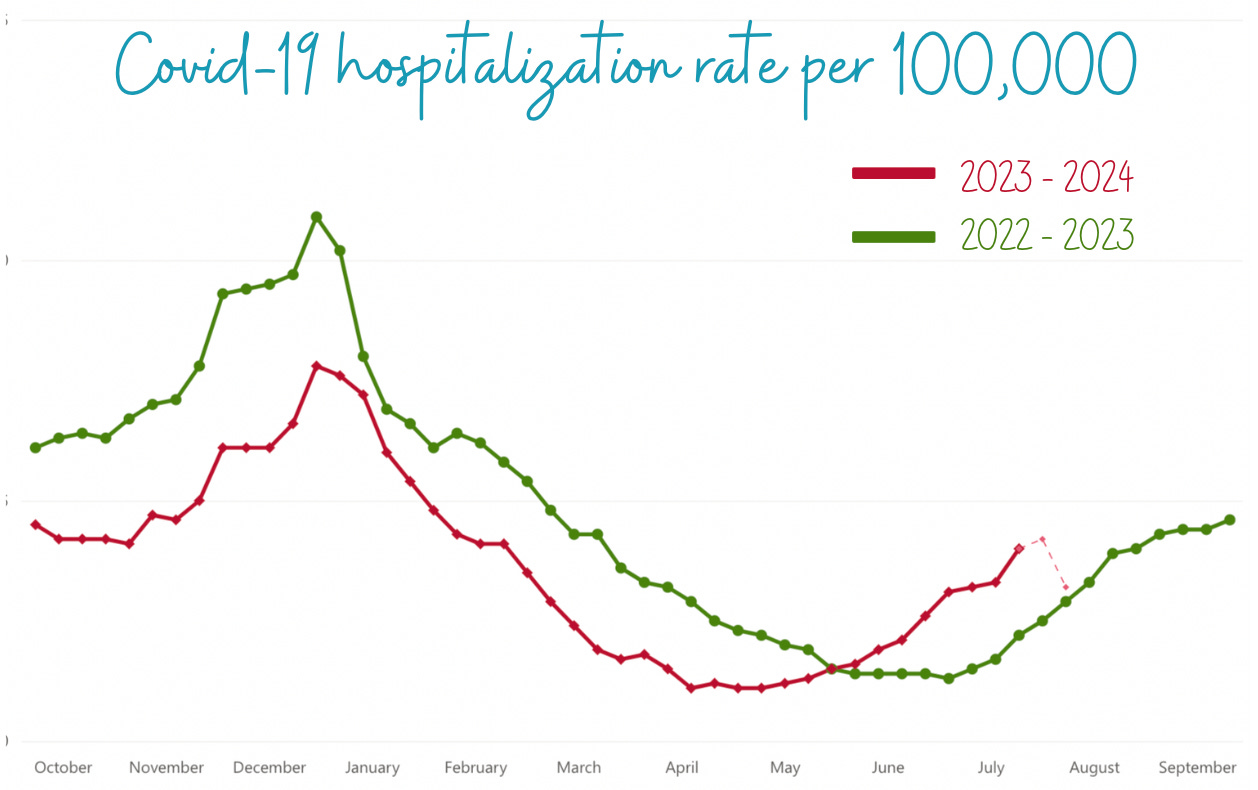

Hospitalizations are also increasing, which isn’t surprising given that it’s a lagging indicator, but levels remain lower than the winter peak. This past week, we lost 1,000 Americans to Covid-19.

Note for the data gurus: Last April, hospitals were no longer required to report Covid-19 data, decreasing reporting from 90% to 38% of hospitals. However, there’s good news: Starting November 1, hospitals will report again! Thanks to all who submitted comments to Health and Human Services. It made a difference.

Mpox: An International Emergency

Last week, Africa CDC declared their first-ever public health emergency for mpox. The World Health Organization (WHO) followed by also declaring a public health emergency of international concern, signaling that the WHO Emergency Committee believes the current mpox outbreak in Africa is:

Unusual and unexpected

Has the potential for cross-border transmission, and

Requires coordinated international response.

This is the right call, and is important, as it (hopefully) draws attention and much-needed resources to the outbreak.

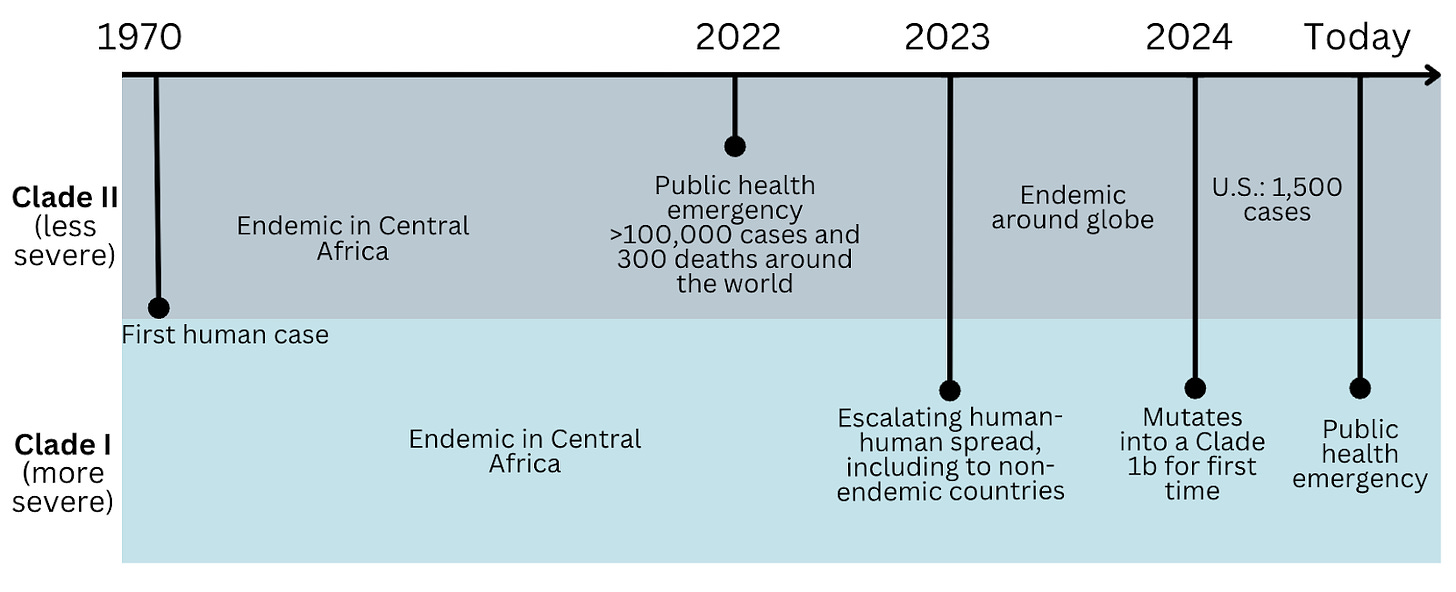

Back up—how did we get here? Mpox (formally known as monkeypox) has been endemic in Central Africa for decades, with rare, sporadic human cases of mpox after contact with infected animals.

However, in 2022, the virus—and specifically a strain considered less severe called Clade II—mutated and caused a massive international outbreak by spreading among a tight-knit social network: men who have sex with men (MSM). Education efforts, immunity, and antivirals have kept mpox spread low since. In 2024, the U.S. has had 1,657 cases of Clade II.

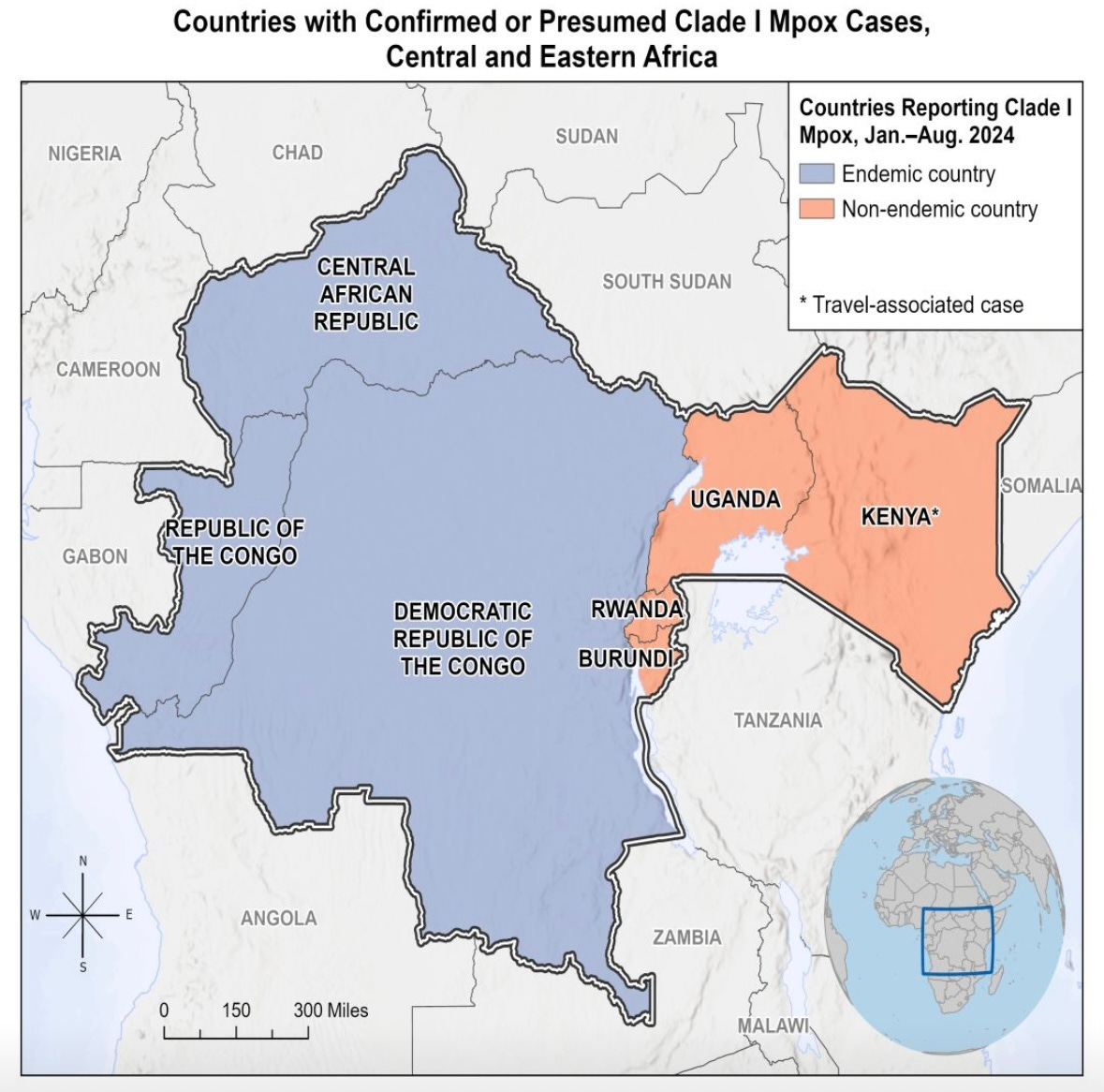

This brings us to today. Clade I—the other mpox strain, historically more severe—is now exploding in Africa, accounting for more than 17,400 cases and 500 deaths. (The true number is likely much higher due to significant under-detection and under-reporting.) Recently, Clade I has spread to non-endemic African countries, and over the weekend, 1 travel case was detected in Sweden.

The majority of cases are the Clade Ia subvariant, with more than 80% of cases being among children and accounting for 85% of deaths. The second subvariant, Clade Ib, is spreading among adults.

No Clade I cases—regardless of subvariant—have been identified in the U.S.

What do we NOT know?

What is Clade I’s dominant mode of transmission? There is overwhelming evidence that Clade II is spread through close contact, like sex. For Clade I, the at-risk population is different. Situation reports show transmission through multiple means: sexual contact, household contact, non-sexual contact (like healthcare exposures), and animal exposures. Experts on the ground do not see epidemiological evidence of airborne spread in Africa; they see, for example, cases of kids hunting squirrels or people in close contact in houses, like four kids in one bed. While there are documented cases of airborne transmission, what is possible isn’t always probable.

How does the fatality rate apply to this Clade and other geographies? Historically, Clade I has a *very* high case fatality rate of 10% (compared to Clade II with <1%). However, it’s unclear whether this high rate is due to the intrinsic properties of the strain or is an artifact of under-detection, poor access to treatment, lack of healthcare, and poor nutrition in Africa. Data, such as an animal model and one small epidemiological study, have confirmed Clade I is more genetically virulent.

How effective is TPOXX (the antiviral) against Clade I? A recent study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo found that while TPOXX was safe, it did not significantly shorten the duration of pox lesions in Clade I cases. The overall death rate and lesion duration among participants were lower than expected among all participants regardless of whether they received TPOXX or placebo, likely due to the high-quality care provided during the trial.

How big will this outbreak be? Due to travel routes, we expect more international cases, especially in European countries. According to CDC modeling, any outbreak of mpox Clade I is expected to be smaller among the MSM community than the 2022 mpox Clade II outbreak.

Scientific teams are working on more lab and epidemiological studies as quickly as possible, which is incredibly challenging in resource-constrained areas.

So, what are we supposed to do? What matters now is that African countries can access vaccines, treatments, and the resources to run important studies to stop this epidemic.

In the U.S., only Clade II is spreading, so those eligible for the mpox vaccine have not changed: gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, transgender or nonbinary people. Make sure you get both doses to be fully protected. For everyone else, there’s nothing to do for now.

Parvovirus B19: Increasing

In the U.S., parvovirus B19—a very common airborne respiratory virus, also known as fifth disease or “slapped cheek” rash—has increased to higher than “normal” in recent months, particularly in children ages 5 to 9. CDC urged physicians to be on the lookout.

The exact reason for the current rise is unknown, but the virus typically spikes every 3-4 years, usually as it starts to warm (late winter to early summer).

Importantly, this virus is not dangerous to the general public. In fact, 50% of people have immunity by the time people reach 20 years old. However, three groups are at high risk because the virus attacks the cells that make red blood cells. This can result in short-lived anemia before the immune system controls the infection.

Pregnant: The virus can cause heart failure in the fetus and miscarriage.

Immunocompromised: The anemia can be long-lasting.

People with conditions that speed up the breakdown of red blood cells (like sickle cell): The anemia will likely be more severe and might require blood transfusions.

Unfortunately, this virus mainly spreads asymptomatically before flu-like symptoms arrive. Because the virus spreads through the air, masking is expected to help.

Bottom line

Covid-19 infections are still surging, and another virus—parvovirus B19—is also rising. There are things you can do—stay up to date on vaccines, mask indoors and in crowded areas, and get that indoor air flowing. Concurrently, the international community has another mpox emergency—for the U.S., though, those at high risk are still men who have sex with men. As always, we’ll keep you updated as things change.

Love, the YLE Team

P.S. Thanks for all of your questions about fall vaccines! We are putting together a series of posts. Expect these in your inbox soon.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment