------------------------------------------

More of your H5N1 questions answered

About the response, steps to protect ourselves, and risk. Also, a note about the LA fires.

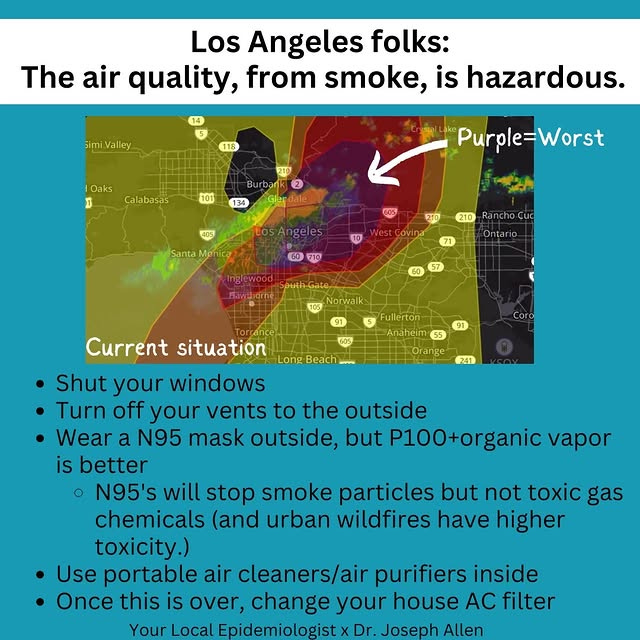

First, a note. This Southern California girl is devastated by the news of the Los Angeles fires. The past few days have been catastrophic and personal; so much lost in a city where I grew up, where family and friends are fleeing, and the destruction keeps coming. It’s hard to comprehend the scale. I hope those of you in LA are staying safe. Remember smoke air is hazardous for your health, but there are a number of things you can do. Hang in there.

Now, onto another public health development: H5N1.

Man, you guys have a lot of great H5N1 (bird flu) questions. Thanks for sending them. It brought flashbacks to the height of the pandemic when I would get thousands of emails.

Here are some answers to the most common ones. Hope this helps!

(Note: This is a follow-up to the last post; read that before diving into this.)

Outbreak/response questions

If human-to-human transmission started, what would the most prominent transmission pathways be (e.g., surfaces, viral suspension in aerosols, droplets, etc.), and would the kinds of N95 masks used for COVID prevention be more/similarly/less effective for H5N1?

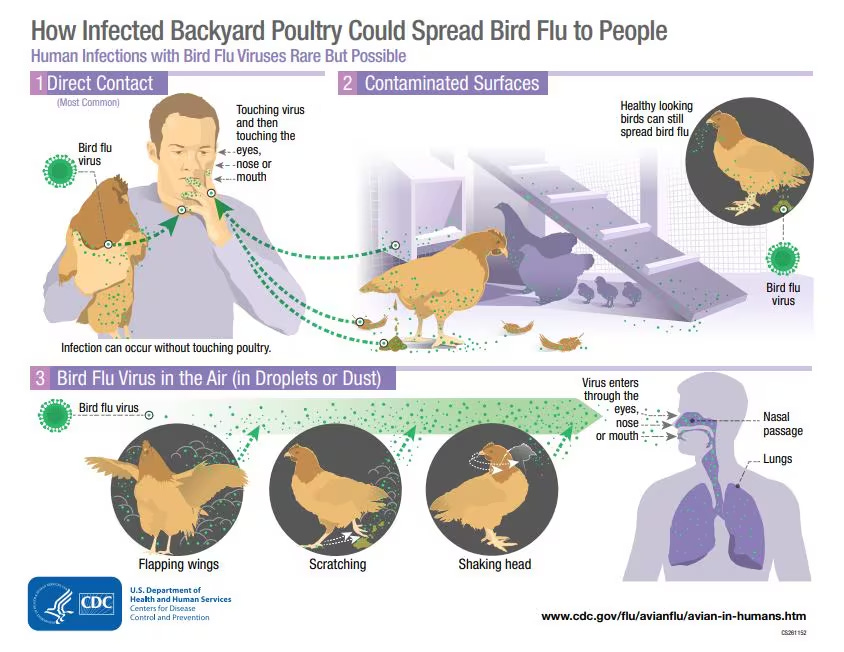

Right now, H5N1 is spreading predominantly through surfaces and direct contact with sick animals (see more in #3).

However, historically, flu strains start as GI infections in birds and become respiratory infections in humans as part of natural selection once they mutate.

So, if this becomes a pandemic, odds are it would look like Covid-19 and other flu pandemics—spread in the air. Contaminated surfaces are a possible source of infection, but less probable.

So, a mask would help, especially the kind that filters our viruses in the air, like N95 masks, as well as ventilation and physical distance. Since H5N1 has also frequently caused eye infections, eye protection may be needed.

Do you know why we aren’t vaccinating our farm and livestock workers?

The U.S. has a stockpile of 4.5 million H5N1 vaccines (although they are based on an old mutation formula, and it’s unclear how well they would work). Other countries, like Finland, have started vaccinating farmworkers.

Three main reasons why we haven’t started in the U.S.:

Disease. Most vaccines are better at preventing severe disease than transmission, and we haven’t seen severe disease in farm workers. (The two severe cases in the U.S. were from backyard poultry and an unknown source.) Sick workers are provided with Tamiflu, which also helps with severe disease.

Potential downsides. For example, there may be rare but real side effects of the vaccines, like Guillain Barre Syndrome.

Uptake considerations. Any vaccine program would be voluntary, and with limited trust in government among high-risk groups, it’s unclear how many would get vaccinated. Also, H5N1 vaccines are two doses, and getting a second dose to a transient population would be challenging.

What would trigger us to use vaccines? It’s unclear, but I assume severity of illness and human-to-human transmission.

How is H5N1 spreading to different dairy herds? Is it through wild birds, chickens, farmers acquiring infected cows, or another way?

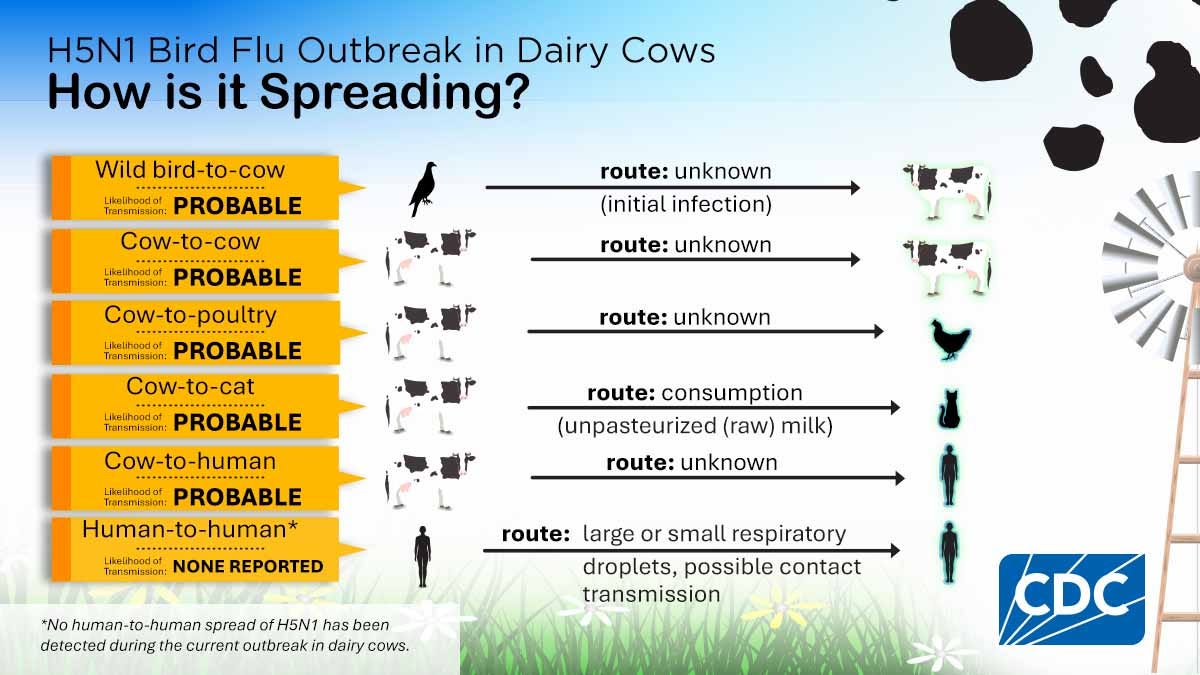

Mainly through milking equipment and the physical movement of cattle. Genomic data show there has been only one spillover event thus far, meaning that cows aren’t generally getting it from wild birds. The cows, however, are spreading it to other animals, as shown in the figure below.

This figure does not include all the pathways from birds. Infected wild birds and poultry can infect humans and other animals.

Is CDC at least doing random sentinel testing of all Flu A samples for H5N1?

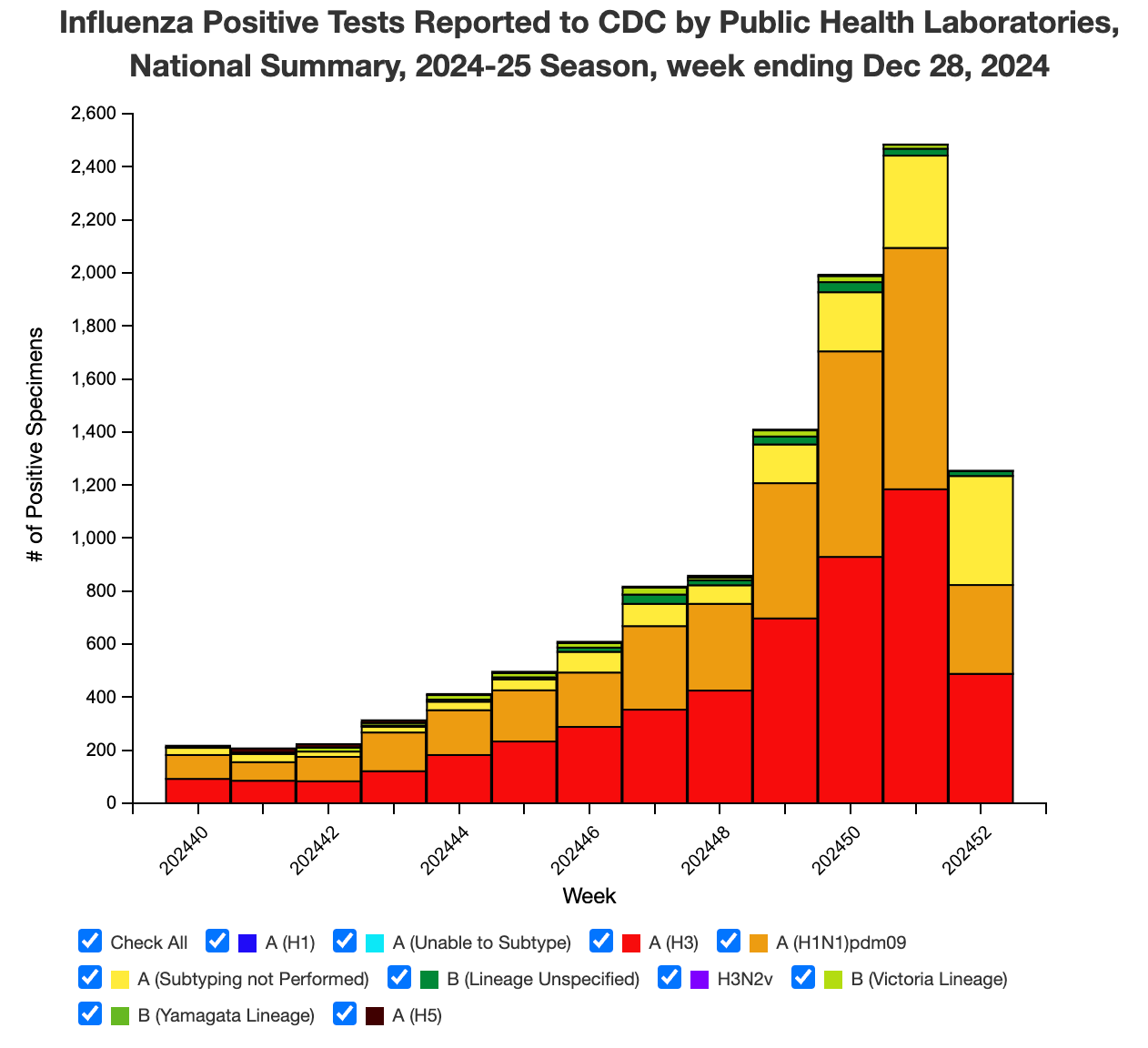

Yes, the U.S. already has a testing network set up (before H5N1 outbreak) because epidemiologists have always been concerned about a potential flu pandemic. CDC tests hundreds of flu samples a week randomly from around the nation.

The latest data show that 1731 specimens of the Flu A tests sent to labs last week were randomly tested; 0 were positive for H5N1. This system isn’t without limitations (sometimes it can feel like finding a needle in a haystack), but if H5N1 did start spreading, we would eventually see it here.

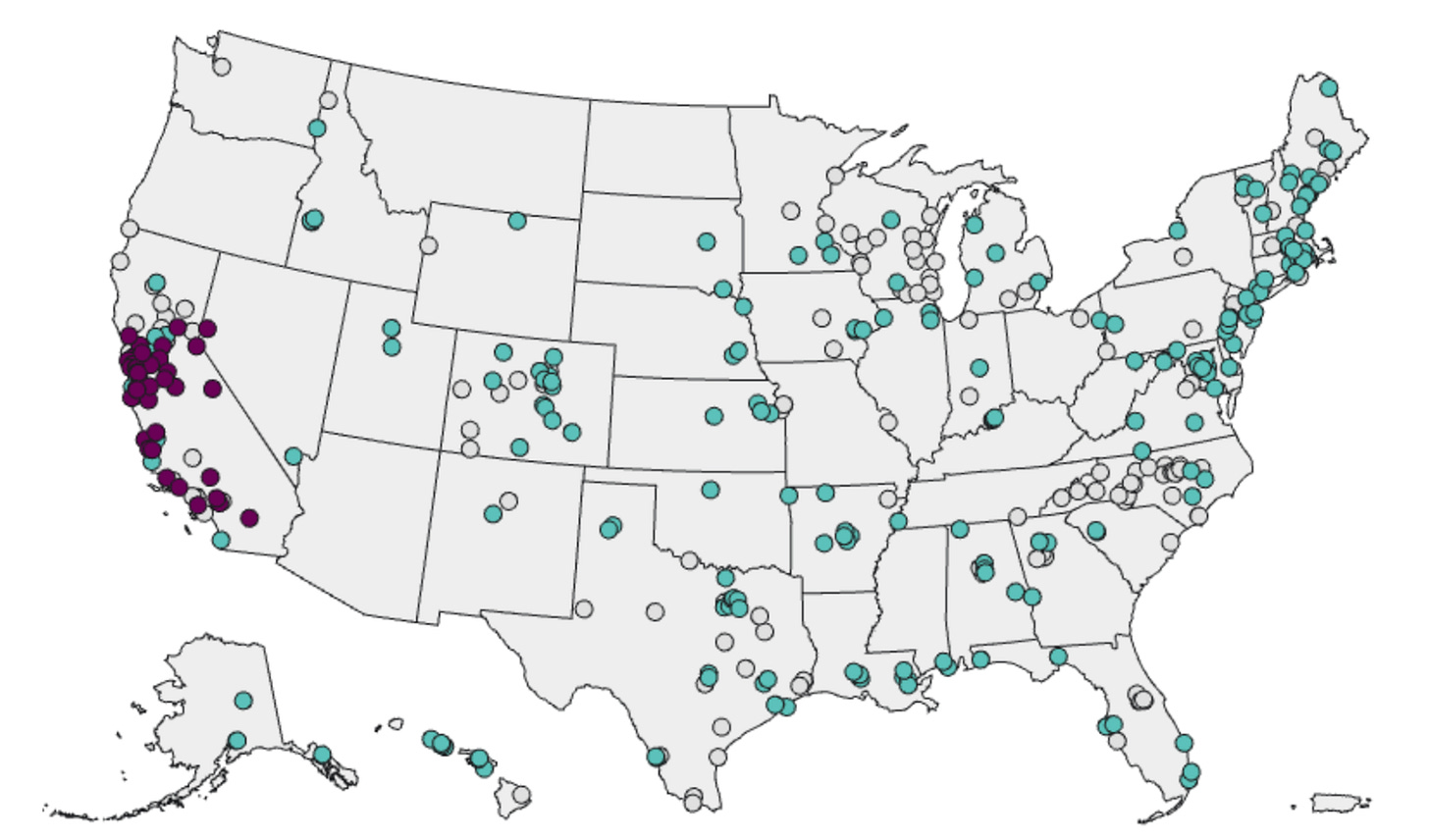

I just saw this wastewater figure on CDC’s website. What is going on in California to cause this and what are they doing about it there?

We’re seeing a lot of virus in California’s cows and birds. California is the number one state for dairy cattle, and so far, 703 herds have tested positive for H5N1. That’s more than 2/3 of all the dairy farms in the state. Plus, 93 commercial or backyard poultry flocks, accounting for about 22 million animals, have also been infected.

Unfortunately, we don’t have the wastewater testing capabilities yet to differentiate between humans and animals. A recent preprint showed wastewater is picking up viruses from animals (rather than humans) through milk dumping, animal sewage, and bird contamination. We are also relying on epidemiologists’ accounts on the ground to sort through the signals.

Detecting more cases

I’m a primary care pediatrician and most of the Flu A cases I’ve been seeing oddly have mild conjunctival injection. What are the odds we are significantly underdiagnosing H5N1 in humans who don’t work with cattle/poultry? How do we know it’s not just limited to those with direct contact still? Simply the fact that severity of disease would be hitting much higher levels at this point if it truly was spreading?

We are almost certainly missing cases from direct animal contact; we don’t know how many, but studies have confirmed that some workers have antibodies but no known infections. People in the hospital with severe flu should get subtyped within 24 hours so we know what strain is infecting them. Quest and ARUP are offering testing now for outpatients, which is helpful.

We would know a pandemic was unfolding by triangulating many sources: abnormal hospital severity rates of flu, random lab testing (see #4 above), wastewater (see #5 above), syndromic surveillance (i.e., looking to see if there are more eye infections in the ED than normal), and more.

I’m surprised there were no screening questions at the hospital, such as “Have you recently been in contact with any birds or dairy cows?”

Asking this question is part of the CDC’s clinical testing guidance, but CDC needs to push it further so physicians are more aware.

Protecting self, family, and pets

We sometimes drink raw milk [...] but we’re in New Hampshire, far away from any dairy herd outbreaks. I assume they would notice if their cows were sick? Or have a low probability of infection since they’re far removed from affected herds?

They should notice if their cows are sick. But the disease is less obvious in cows than in poultry, where they drop dead. The main symptom among cows is decreased milk supply.

Even though no positive herds have been identified in your state, that doesn’t mean there aren’t any. Given voluntary testing and reporting, we are largely flying blind. We simply don’t know the full scope of the spread.

In December, a federal raw milk testing program started in 28 states representing 65% of the nation’s milk production (results are not available yet): California, Colorado, Michigan, Mississippi, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Maryland, Montana, New York, Ohio, Vermont, Washington, Alabama, Arizona, Delaware, Iowa, Georgia, Kansas, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia.

Bird poop, like on golf courses. How concerned should we be?

Risk is dependent on two things: the amount of virus you’re exposed to and the duration. For example, the severe H5N1 human cases have been from birds. The hypothesis is that they inhaled a massive dose of virus when handling a dead bird.

It’s unlikely to get infected by a stray piece of bird poop on a golf course, for example. While bird poop can harbor high loads of viruses, it goes away over time. People are getting infected mainly by touching their faces with contaminated matter or breathing it in (#3 above). So wash your hands.

What is the risk to bird hunters and their retrieving dogs?

Hunters are at high risk for H5N1, especially if they don’t use PPE while handling dead birds. A Washington study showed that 2% (4/194) of hunting dogs tested positive for H5N1.

You mentioned exposure to H5N1 through raw milk; what about over-easy eggs?

Birds have a high H5N1 mortality rate, so they are unlikely to produce eggs if sick. Given that H5N1 has been around for a while among birds, poultry farms also have a very rigorous detection and culling process. (It significantly impacts their bottom line!)

So your eggs are likely safe, but you should cook eggs nonetheless, given other risk factors. ;)

Bottom line

Keep those questions coming. We will keep a close eye on H5N1 and update you on any major developments.

Love, YLE

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE) is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, Dr. Jetelina runs this newsletter and consults with several nonprofit and federal agencies, including CDC. YLE reaches more than 296,000 people in over 132 countries with one goal: “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people feel well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment