-----------------------

H5N1 Update: January 7

First bird flu death in the U.S., my level of concern, and FAQs

H5N1 has been dominating headlines and social media. Yesterday, the first H5N1 (bird flu) death was reported in Louisiana—a tragic reminder that H5N1 is a very dangerous virus, and we’ve been, quite frankly, lucky so far.

The risk of H5N1 is still low to the general public, but here are the latest developments, what I see through the inkblots, and answers to FAQs.

H5N1 keeps spreading among animals

H5N1 is an old virus established in wild birds 25 years ago. In 2021, a variant called clade 2.3.4.4b started to spread among birds, like poultry, and mammals worldwide. Then, in 2024, we saw it spread from cow to cow for the first time in the U.S. This was unexpected, as we don’t typically see flu in cows, but this is also what flu does—unexpected things.

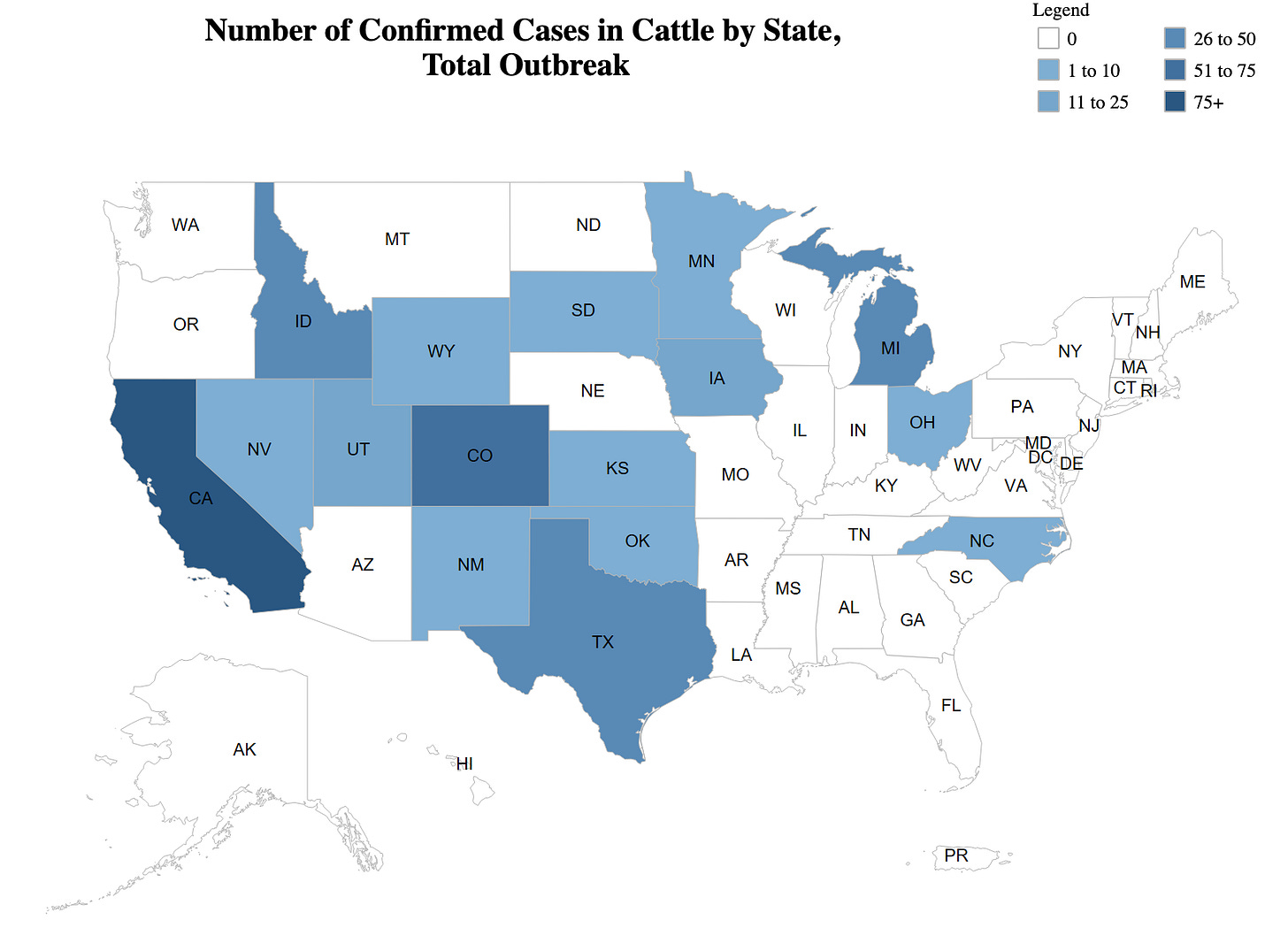

Since, H5N1 hasn’t stopped spreading. (It certainly has not burned out as the USDA continues to hope for.) The latest tally of known infections includes:

10,922 wild birds,

917 dairy herds, and

130,674,361 poultry— a big reason why eggs are hard to find and expensive.

Spread among animals, particularly those in close physical proximity to humans, means we continue to see “spillover” infections to humans. In other words, the virus keeps jumping from animal to human, which is bad because every time it jumps, the virus can mutate.

CDC has tallied 74 human infections thus far (67 confirmed + 7 probable). However, because testing is limited, we could be missing many infections, especially the milder ones that don’t make people seek care.

People are mostly getting sick from direct exposure to sick dairy cows (44 people) or sick poultry in massive operations (23 people). Thankfully, we have not seen human-to-human transmission. The virus hasn’t mutated to do so yet.

It was only a matter of time until we saw severe cases

Historically, H5N1 has caused severe disease, so this death shouldn’t be a surprise. While the WHO cites a 50% mortality rate from H5N1, this is likely a gross overestimate due to the underdetection of human cases who have mild or asymptomatic diseases.

Out of the 74 American H5N1 cases, we’ve had two severe cases:

Louisiana: Older adult; infected from their backyard poultry. This patient died.

Missouri: Older adult; it’s unknown how they got infected.

Notably, there has also been a severe case among a teenager in Canada who was fighting for their life. (A recent NEJM case study described how severely sick she was.)

There aren’t enough human cases to start drawing patterns of severe disease. But historically, the flu has been unkind to those with weaker immune systems, including children, older adults, and those with comorbidities. Thus far, we have seen severe disease only among these groups. Also, we know some severe cases had exposure to a ton of virus (as opposed to cases from dairy milk, where viral levels are lower.)

We don’t know the “true” mortality rate, but as we learned during Covid-19, even a small percentage of a large number of people is a large number. If H5N1 turned into a pandemic, it could be devastating.

Why are experts so concerned?

In the past year, H5N1 has taken up a lot of brain space for epidemiologists, virologists, and veterinarians alike. As Dr. Michael Osterholm said to STAT, “Any time you’re dealing with H5N1, you sleep with one eye open.”

There are a few reasons for the continued anxiety:

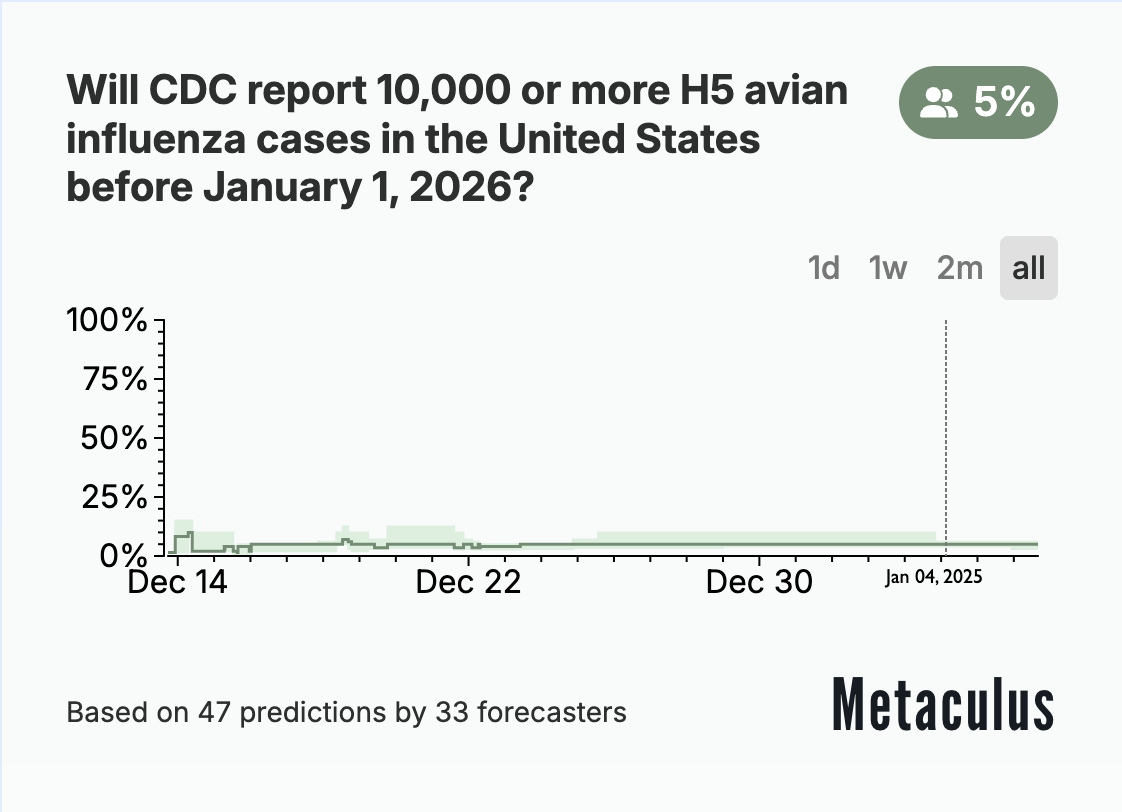

Low probability, high consequence event. The probability of a pandemic in any given year is 2%. Spillovers happen all the time, but very few become pandemics because many unlucky things must occur in sequence. The situation unfolding with H5N1 has increased the probability. CDC placed the potential risk of H5N1 to humans as “moderate,” and Metaculus (who hosts a CDC-sponsored respiratory disease forecasting tournament) places the probability of a pandemic in the next year at 5%. In May 2024, I wagered 5%. I now think it’s 7-9% given that H5N1 continues to spread largely unchecked.

It’s flu season. If the same person is infected with seasonal influenza, H5N1 could “swap” genes, causing a mutation that sends human-to-human transmission.

New mutations. The Louisiana patient developed new H5N1 mutations, which increased its ability to bind human cells. This isn’t surprising (viruses change) but shows what the virus can do.

Lack of urgency in the U.S. government, particularly USDA. The time to stop a pandemic is now, and it needs to be stopped at the source—that’s animals. This is USDA’s lane, but priorities, agility, experience, and politics differ from those of the agencies dealing with human health. We are still flying blind. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) finally allocated $306 million to bolster the nation’s human preparedness for H5N1, including giving $183 million to regional, state, and local programs.

Unanswered questions. Of course, like with any outbreak, there are endless questions: Do these severe cases have a more severe strain than others? What is causing the H5N1 spikes in wastewater? Will the stockpile of vaccines be effective?

But should you be concerned?

Experts’ anxiety has percolated to the public. I tell my friends and family: H5N1 is something to watch, but don’t let it take up too much headspace yet. Risk lies with agriculture workers and those in contact with sick birds. (Raw milk can potentially cause severe disease, but there have been no cases yet.)

And, for the general public, there’s not much you can do. Don’t drink unpasteurized milk. Don’t touch wild birds. And if livestock animals look sick, stay away. (If you have backyard poultry, check out this last YLE post, which includes using PPE.)

When should alarm bells go off? A DEFCON 1 YLE email will land in your inbox. But, more seriously, concern should rise when your risk rises. That will happen if we see human-to-human transmission.

More subtle signs of changing risk include:

H5N1 starts spreading among pigs (they are great mixing vessels and could cause a mutation more quickly)

Worrisome mutations spreading among animals

Question Grab Bag

We continue to get a lot of great questions on H5N1. Here are some answers not touched on above:

Flu is spreading right now. How do we know that some of these cases aren’t H5N1? Unfortunately, rapid Flu A tests cannot differentiate between a positive for seasonal flu or H5N1. We rely on clinicians to decide whether more testing is necessary, usually triggered through symptoms (like red eyes for H5N1) or history (like exposure to sick animals). While it is possible that some of the flu cases are H5N1 infections that we’re missing, it’s not particularly likely (for now).

Do I need to “prep” for a pandemic this year, like stocking up on Tamiflu? Tamiflu does work against H5N1, but please don’t stockpile. We are in peak respiratory flu season—people need access to antivirals.

Do seasonal flu vaccines work against H5N1? The short answer is we don’t know. H5N1 has some important similarities to H1N1 (seasonal flu) proteins, so some antibodies and T-cells could cross-protect. But other lab studies show it’s imperfect. If H5N1 did become a public health emergency, we would almost certainly need H5N1 vaccines. About 4 million are stockpiled, but we don’t know how well they will work in the real world, especially if H5N1 mutates. mRNA vaccines are being developed as we speak.

Can this affect my pets? Domestic animals—cats and dogs—can get H5N1 if they contact (usually eat) a dead or sick bird or even its droppings. The current cow outbreak revealed another infection pathway: unpasteurized milk. Fifty percent of cats that drink raw milk died.

What about bird feeders? Birds that gather at feeders (like cardinals, sparrows, and bluebirds) do not typically carry H5N1. The USDA does not recommend removing backyard bird feeders for H5N1 prevention unless you also care for poultry. The less contact between wild birds and poultry (by removing sources of food, water, and shelter), the better.

Bottom line

The H5N1 outbreak marches on, but only keep H5N1 as a small nugget in your headspace for now. If risk changes (which it can quickly), I will let you know at the very least.

In the meantime, the U.S. government needs to take control of this outbreak. The time to prevent an H5N1 pandemic is now.

Love, YLE

Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)

is founded and operated by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH PhD—an

epidemiologist, wife, and mom of two little girls. During the day, Dr.

Jetelina runs this newsletter and consults with several nonprofit and

federal agencies, including CDC. YLE reaches more than 296,000 people in

over 132 countries with one goal: “translate” the ever-evolving public

health science so that people feel well-equipped to make evidence-based

decisions. This newsletter is free to everyone, thanks to the generous

support of fellow YLE community members.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment